Hernán Cortés and the Conquest of México

The Book of the Month for November 2025 is The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards written by Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra (1610-86). Worth’s copy is the 1724 edition that was published in London and translated into English by Thomas Townsend. It is more than likely that Worth bought this book brand new and had it bound in the 1720s as it bears some of the characteristics of other books in his collection which were bound by ‘Parliamentary Binder A’: i.e. it is covered in dark sprinkled calf; the spine is painted black and its compartments are gold-tooled to a centre and corner design using a pair-of-birds centre tool, alternating with a built-up centre design of tulip and spray tools.

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), title page.

The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, follows the journey of Hernán Cortés (1485-1547), a Spanish conquistador, and his conquest of México.[1] At the time, the Spanish monarchs had two reasons for wanting to conquer México. First, they desired the resources and gold that México had in abundance. Secondly, they wanted to spread the Catholic religion.[2] Cortés had to carefully argue his case for conquering México without official permission, for increasingly it became necessary for colonizing nations to justify invading Native land, as it had been determined that Natives were potential souls to be saved and that they should not be harmed unnecessarily.[3] Without this permission, he could be considered a traitor and would face punishment. Eventually, he did receive formal permission to conquer Montezuma II’s empire, but he was carefully monitored by the Spanish government for acts that could be considered treasonous.[4] Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra presents Hernán Cortés’ actions in a positive light because having received official permission to invade and conquer, both the Spanish monarchs and Cortés acted as if that had been the plan all along.

The Author and Translator

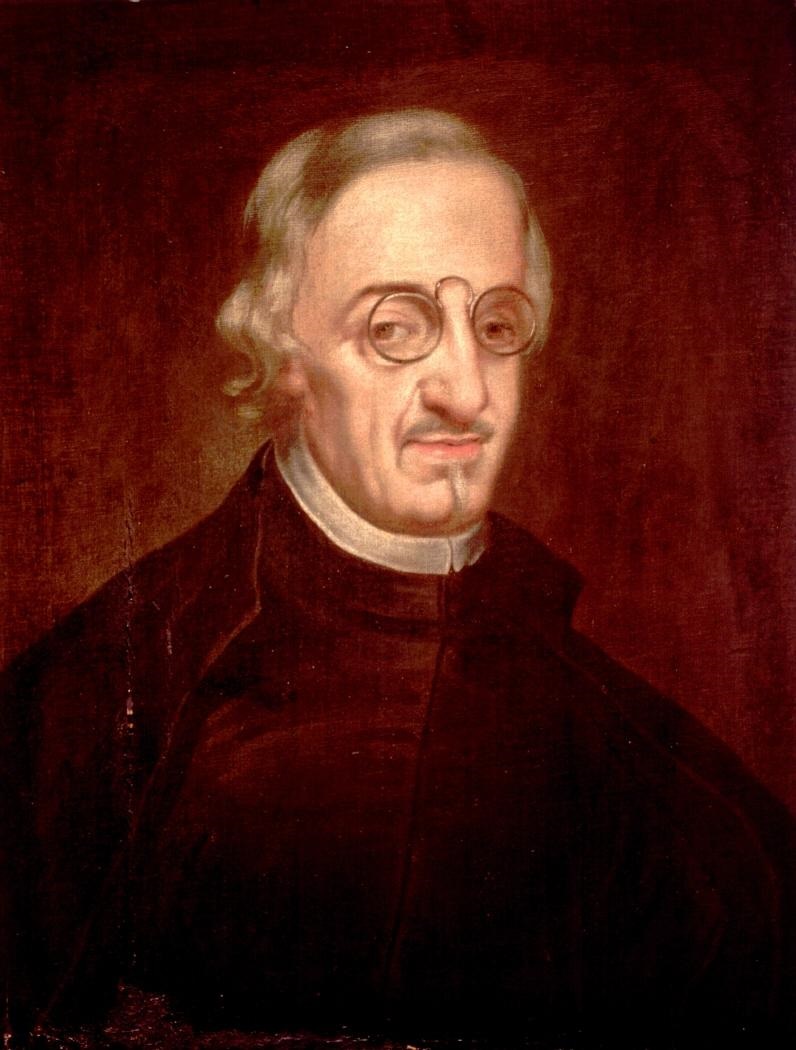

Portrait of Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra by Juan de Alfaro y Gamez, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra was a Spanish poet and historian from Alcalá de Henares. He is famous for his literary output, and, as Chipman notes, ‘In Spain’s Golden Century Solís was renowned as a man of letters and a gifted poet. As such he moved in a circle of extraordinary talent that included Velásquez and Pedro Calderón de la Barca. His connections at court plus his reputation as a writer ultimately won Solís the position of Cronista Mayor de Indias’.[5] However, after being asked to be the official chronicler and cosmographer of the Indies during Phillip II’s reign, he quit writing poetry. He was known for his critiques of other writer’s work, often issuing trenchant criticisms:

‘Bernal Díaz was criticized for disparaging the heroic image of Hernán Cortés; Herrera was dismissed as one who attributed ‘efectos grandes a causas ordinarias’; Gómara was condemned to the anonymity of ‘dicen algunos escritores’; Las Casas was accused of rank dishonesty; and Oviedo was virtually ignored. Only in the case of Acosta did Solís acknowledge a man of sound judgment’.[6]

These criticisms reflect the ones that Thomas Townsend, the translator of the English version, makes against other historians regarding their portrayal of Cortés. Little is known about Thomas Townsend. His translation opens with a dedication to James Brydges (1673-1744), Duke of Chandos, and in it Townsend portrays Cortés as a hero, arguing that opponents of Cortés, such as Francisco López de Gómara (1511-64), Antonio de Herrera, and Bernal Díaz del Castillo (1496-1584); ‘either took Things too much upon Trust, or were prejudic’d against him’.[7] Townsend claims that it was, ‘The great Actions of Cortez, and the elegant Pen of Solis’, that inspired him to translate the history into English.[8]

Townsend’s purpose in translating Solís’ text appears to stem from a desire to emulate the work of contemporary translators who likewise focused on translating texts dealing with the conquest of the Americas. He mentions that ‘Sir Paul Rycaut having translated the Conquest of Peru from Garcillasso de la Vega, Inca, my present Work compleats the Discovery and Conquest of the American Continent’.[9] Sir Paul Rycaut (1629-1700) was an author, diplomat, and historian who graduated from Trinity College, Cambridge. While he was better known for his works about the Ottoman empire, he was also famous for translating works from Greek and Spanish to English, such as The Conquest of Peru, which had been written by Garcilaso de la Vega the Inca (1539-1616).[10] Garcilaso de la Vega the Inca had been born in Peru, his father a Spanish conquistador, and his mother a member of Incan royalty. As a result, his magnum opus on the conquest of Peru (which Worth owned in a 1633 Parisian French edition), had incorporated Incan as well as Spanish accounts. Townsend’s translation was thus conceived as a bridge connecting the whole historical narrative of the Spanish conquest of the Americas for an English-speaking audience.

Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar

Portrait of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar. John Carter Brown Library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The figure of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465-1524), looms large in De Solís y Ribadeneyra’s account of the conquest of Mexico. Velázquez, who was born in Cuéllar, Spain, had first come to the Americas in 1493 with Christopher Columbus (1451-1506).[11] De Solís y Ribadeneyra tells us that on his second voyage to the Americas he had been in the company of Diego Columbus (1479-1526), also known as Diego Colón: ‘The Island of Cuba was at that Time governed by Captian Diego Velasquez, who went thither as Lieutenant to the second Admiral of the Indies, Don Diego Colon [Son of Columbus], with such good Fortune, that the Conquest of it was owing to him, and the greatest Part of the Settlement’.[12] It was Diego Colón who was responsible for encouraging Diego Velázquez and Hernán Cortés to sail to and conquer Cuba in 1511.[13]

Velázquez de Cuéllar organized the initial explorations of México by Cortés, but he soon became suspicious of Cortés’ actions and reversed the order.[14] As Pagden and Elliott note:

‘Diego Velázquez … was merely the deputy of the hereditary admiral of the Indies, Diego Colón (Columbus). Velázquez, however, was an ambitious man, eager to conquer new lands in his own right. To do this, he must somehow break free from Colón’s jurisdiction, and obtain from the Crown his own license to explore, conquer and colonize’.[15]

Prior to sending Cortés, Diego Velázquez had already sent two initial exploring expeditions in 1517 and 1518 (the second expedition having permission from the governors of Hispaniola, who were not under Diego Colón’s command).[16] Velázquez was attempting to become governor of Yucatán for De Solís y Ribadeneyra tells us that ‘He had also dispatched, in succession, two personal agents to the Spanish Court – Gonzalo de Guzmán, and his chaplain, Benito Martín – to urge the Crown to grant him the title of adelantado [governor] of Yucatán, with the right to conquer and settle the newly discovered lands’.[17] Because of this, Velázquez had to tread carefully: he needed enough presence in the Yucatán to support his request to be made governor, but he could not do anything that could be considered colonizing, as he did not have official permission to do so.

Velázquez therefore sent several expeditions which he claimed to be trading expeditions. As one of the fleets he sent had yet to return, he sent Cortés on a search party on 23 October 1518. According to Velázquez’s instructions, ‘The purpose of Cortés’s expedition, according to these instructions, was to go in search of [Juan de] Grijalva’s [1489-1527] fleet (of whose return to Cuba Velázquez was still unaware), and of any Christians held captive in Yucatán. Cortés was also authorized to explore and to trade, but had no permission to colonize’.[18] Velázquez trusted Cortés enough to send him to México and to follow his instructions, but he soon learned that his trust was misplaced. The moment Cortés disobeyed the orders of Velázquez, he started a legal fight for the right to colonize and govern México that would span the course of many years.

Hernán Cortés

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), plate facing Book I, p. 33, portrait of Hernán Cortés (1485-1547).

One cannot understand the history of the conquest of México without understanding Hernán Cortés. In The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, it states that, ‘He was born in Medillin, a Town of Estremadura, Son of Martin Cortes, of Monroy, and Donna Catalina-Pizarro Altamarino’.[19] Cortés was studious in his youth, but according to De Solís y Ribadeneyra ‘the sedentary Application of a Studious Life, was contrary to his Temper, and did not suit the Vivacity of his Spirit’.[20] His studious background explains how he was able to masterfully argue his case for conquering México without permission, and avoid being put in prison for treason.

According to De Solís y Ribadeneyra, ‘Cortes was well made, and of an agreeable Countenance; and besides those common natural Endowments, he was of a Temper which rendered him very amiable; for he always spoke well of the Absent, and was pleasant and discreet in his Conversation. His Generosity was such, that his Friends partook of all he had, without being suffer’d by him to publish their Obligations’.[21] Arguably, this description of Cortés by Solís y Ribadeneyra is extremely optimistic at best, and a false aggrandizement at worst. Cortés was not as well-liked as De Solís y Ribadeneyra suggests, and in fact, he was not as virtuous as previously described.

Before leaving Spain, he became engaged to Catalina-Suarez Pacheco. However, upon attempting to end the engagement, he was imprisoned until he agreed to marry her. De Solís y Ribadeneyra carefully omits the circumstances of Cortés’ imprisonment and simply states: ‘He married in that Island Donna Cathalina-Suarez Pacheco, a noble and virtuous young Lady. This Courtship brought him under many Difficulties, by the interfering of Diego Velasquez, who made him Prisoner till such Time as all Differences were adjusted; and then Velasquez stood Father to the Bride, and gave her to him in Marriage’.[22] Furthermore, there were mysterious circumstances surrounding her death many years later, and Catalina’s mother and brother took Cortés to trial for her murder, but he was found to be ‘not guilty’.[23] This leads one to believe that Cortés was not as heroic a man as both De Solís y Ribadeneyra and Townsend made him out to be. Equally, it points to personal reasons behind the hostility between Velázquez and Cortés. However, despite his questionable character, Cortés was considered trustworthy enough by Diego Velázquez to choose him to undertake an expedition to México.

Despite Velázquez’s initial approval of Cortés sailing to México, partway through the voyage, Velázquez sent a letter telling Cortés to return to Cuba. De Solís y Ribadeneyra suggested that cowards had turned Velázquez against Cortés and he claimed that ‘Diego Velasquez hearken’d to their Discourse and tho’ he seemed to be displeased, they discover’d in his Mind a Disposition to Jealousy, easy to be work’d up to an entire Distrust’.[24] De Solís y Ribadeneyra may not, however, be just to Velázquez.

In reality, Velázquez was awaiting approval to colonize México and had numerous reasons to believe that he would very soon be granted the permission that he sought. As Pagden and Elliott report:

‘Ferdinand the Catholic had died in 1516, and in September, 1517, Charles of Ghent arrived in Castile from Flanders to take up his Spanish inheritance. Charles’s arrival in the peninsula was followed by a purge of the officials who had governed Spain and the Indies during the regency of Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros. Among the councillors and officials who acquired, or returned to, favor with the coming of the new regime was the formidable figure of the bishop of Burgos, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, the councillor principally responsible for the affairs of the Indies during the reigns of Ferdinand and Isabella. Fonseca had always had fierce enemies and devoted partisans; and among the latter was Diego Velázquez, who was married to Fonseca’s niece. There was every reason, then, to assume that he would use all his newly recovered influence to support the pretensions of Velázquez’.[25]

This turn of events prompted Cortés to make his own move to gain power, for, as Pagden and Elliott note ‘If he were ever to be a great conqueror in his own right, it was therefore essential for him to act with speed, and to obtain as much freedom for maneuver as possible’.[26] Cortés needed permission to build settlements if he was going to build an empire. The only challenge was how to accomplish this in a legal manner.

The key to Cortés’s success was a clause that allowed him to settle in the case of an emergency. As Pagden and Elliott remind us, due to Article 27, ‘he was now empowered to take such measures as he might consider necessary, and which were not specifically covered by his instructions’.[27] It was a race against time with Velázquez, as to which conquistador would have the legal right to act as governor.[28] Furthermore, because the king was the head of justice, ‘This meant that, from the moment of his departure from Cuba, Cortés totally ignored any claims to jurisdiction of Velázquez or Colón and behaved as if he were directly subordinate to the Crown alone’.[29] Using this justification Hernán Cortés sailed and conquered México, and his success in doing so allowed him to get away with it, though his later actions would be closely monitored by the Crown.

México: Land and People

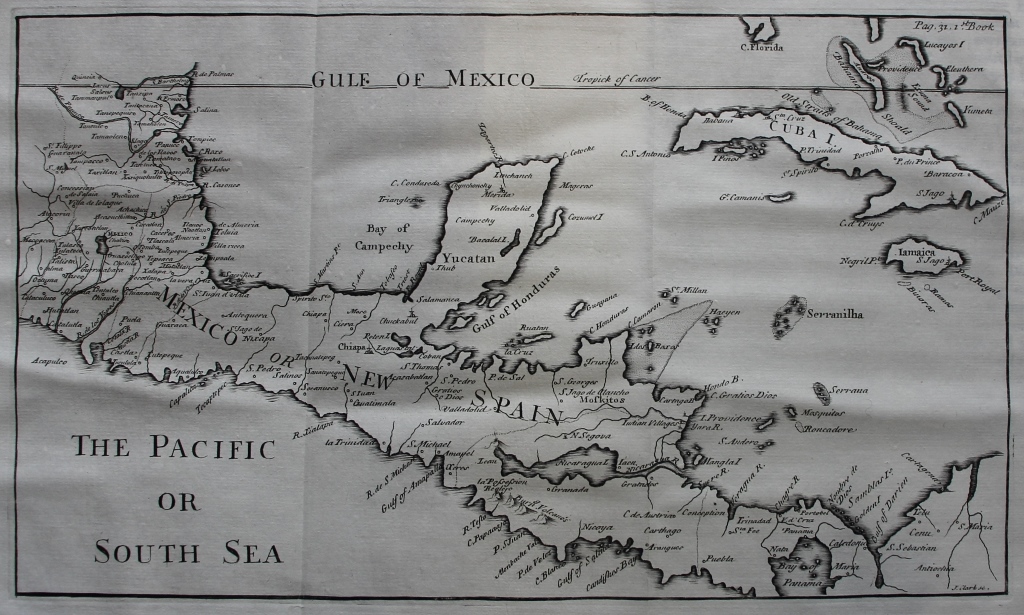

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), plate facing Book I, p. 31, map of Mexico or New Spain.

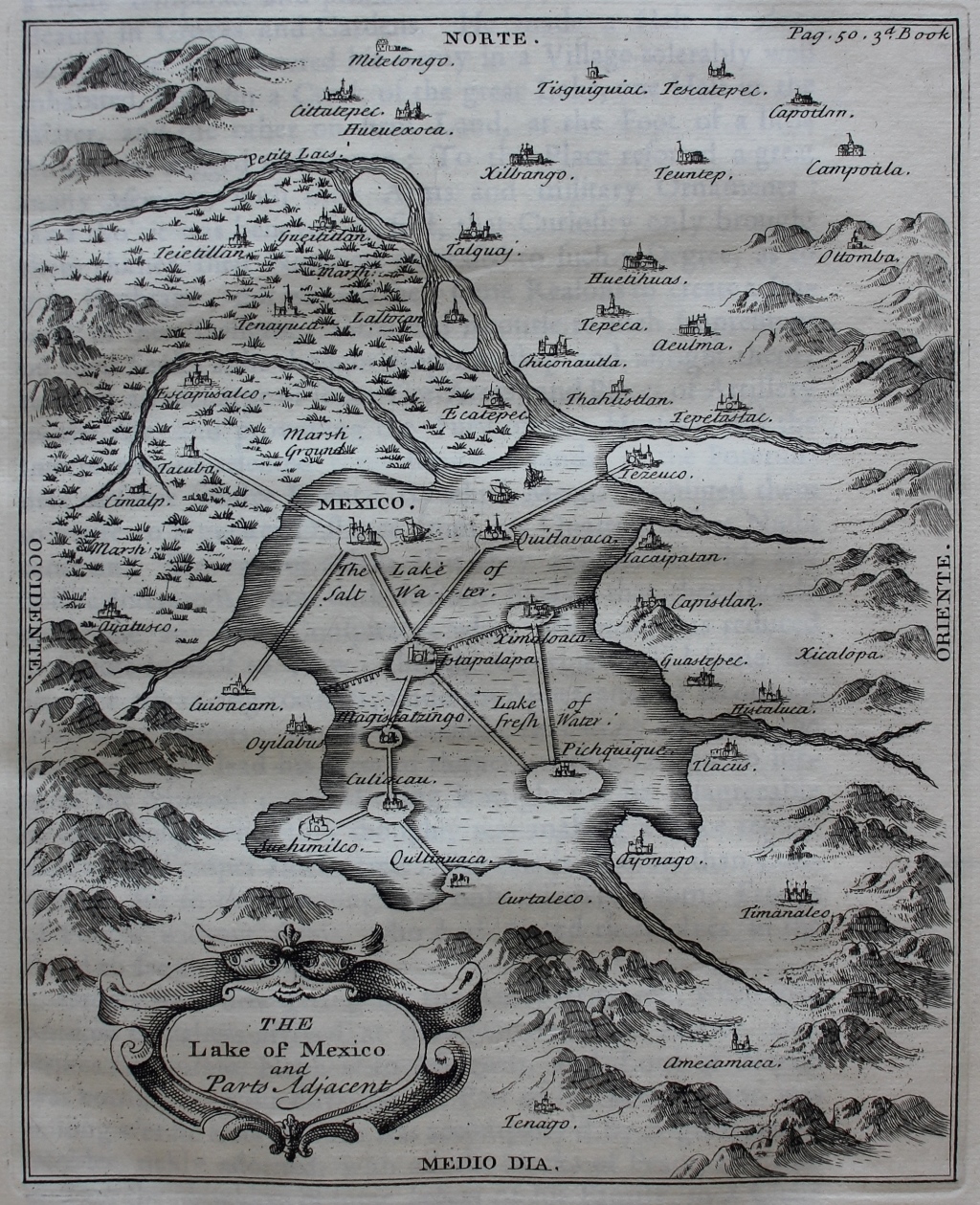

In order to understand Cortés’ success in taking over the Aztec empire in México, it is vital to consider the history and social structure of the Indigenous peoples he encountered. The map above depicts what México looked like at the time of Cortés’ arrival. Tenochtitlan, which was the centre of Montezuma II’s empire, is in the northwestern basin of México at the bottom of the lake. The surrounding towns are named after the tribes that inhabited those areas. This was the area of México where the majority of Cortés’s conquest took place.

It is important to note that the term Aztec refers to both an empire as well as an ethnic tribal group. However, not all of the citizens of the Aztec empire were a part of the Aztec ethnic group, but rather comprised of several distinct tribal groups. As Schmal notes:

‘Professor Smith observes that the Aztecs ‘were the inhabitants of the Valley of México at the time of the Spanish conquest. Most of these were Náhuatl speakers belonging to diverse polities and ethnic groups (e.g., Mexica of Tenochtitlán, Acolhua of Texcoco, and Chalca of Chalco). In short, the reader should recognize that the Aztec Indians were not one ethnic group, but a collection of many ethnicities, all sharing a common cultural and historical background’.[30]

There were long histories of conflict between the tribes. The reason for this is that the dominant group of the Aztecs, known as the Mexica Indians, were outsiders who migrated from the North into the valley of México and then started to dominate the other Indigenous groups that were already there.[31] The México valley was inhabited by seven Náhuatl-speaking tribes: the Xochimilca, the Chalca of Chalco, the Tepaneca, the Acolhua of Texcoco, the Tlahuica, the Tlaxcaltecans, and the Mexica.[32]

The tribes did not coexist peacefully at first, but rather experienced much internal strife. As Schmal makes clear: ‘Sometime around 1428, the Mexica monarch, Itzcoatl, formed a triple alliance with the city-states of Texcoco and Tlacopan (now Tacuba) as a means of confronting the then dominant Tepanecs of the city-state of Azcapotzalco’.[33] The triple alliance defeated the Tepanecs and ruled together. However, as Professor Smith (quoted by Schmal) notes, ‘the three Triple Alliance states were originally conceived as equivalent powers, with the spoils of joint conquests to be divided evenly among them.’ However, over time the Mexica in Tenochtitlán grew to dominate its two partners, Texcoco and Tlacopan’.[34] In addition, the Triple Alliance began to expand its empire, and as it did, it required tribute to be given to it by those whom it conquered. Tribute came in the form of goods as well as humans to be sacrificed.[35]

Human sacrifice was an aspect of the Mexica culture that ultimately contributed to the other tribes aligning themselves with Cortés in his journey to conquer México. Numerous tribes in the region of México had indeed practiced human sacrifice; however, not to the extent that the Mexica practiced it. Furthermore, as Schmal reminds us: ‘The period from 1446 to 1453 was a period of devastating natural disasters: locusts, drought, floods, early frosts, starvation, etc. The Mexica, during this period, resorted to massive human sacrifice in an attempt to remedy these problems. When abundant rain and a healthy crop followed in 1455, the Mexica believed that their efforts had been successful’.[36] The increase in human sacrifice, in combination with a series of disasters and bad omens, led to the decline of the Aztec empire due to individual tribes’ willingness to align themselves with the new conquerors.

Book I: First contacts

Townsend’s English translation of The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, is divided into five books. Each one contains an in-depth description of a small part of Cortés’ journey in conquering México. The books begin by describing the events that took place before he arrived in México, and end with the Natives surrendering to Cortés.

Book I begins with an explanation of the translator’s choice in translating the history of the Indies as a singular, smaller region as opposed to an overarching anthology about the Indies as a whole, which would have included both North and South America. Townsend states: ‘My Design is to recover the History of New Spain out of this Labyrinth and Obscurity, in order to write it separately, placing it, as well as I am able, in a such Light, that the Mind of the Reader may be struck by the Wonderful without being shock’d, and instructed by the Useful without being disgusted’.[37] De Solís y Ribadeneyra had begun his text with a description of the early history of Spain’s involvement in the Indies, and how it changed with the arrival of King Charles I (1500-58) of Spain (Holy Roman Emperor Charles V), after the death of King Ferdinand II (1452-1516). De Solís y Ribadeneyra was quick to laud the actions of Charles V:

‘The Storm began to abate upon his Coming, and the Influence of his Presence, by little and little, introduc’d a Calm. The first Effects of this happy Change were perceived in Castile, whose Tranquillity communicated it self to the rest of the Kingdoms of Spain, and afterwards reach’d to the Dominions abroad; as in a human Body, the natural Heat distributes it self, passing from the Heart to the Benefit of the most distant Members’.[38]

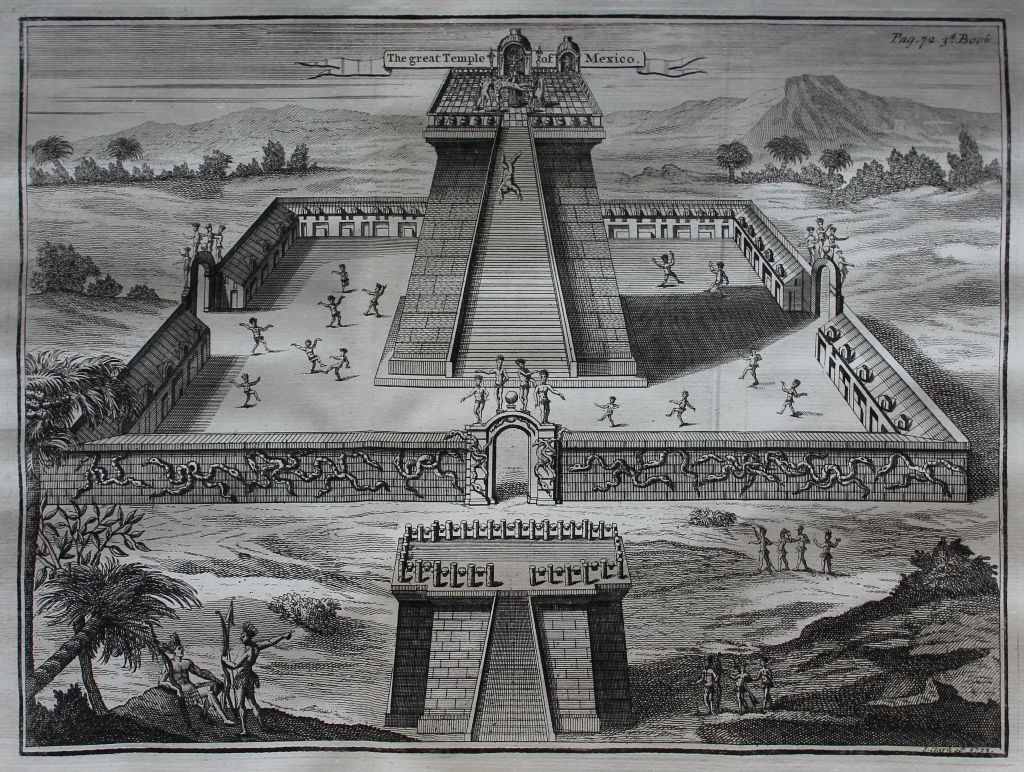

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), plate facing Book III, p. 72, ‘The great Temple of Mexico’.

De Solís y Ribadeneyra then discusses the reasoning behind the decision of the conquistadors to name Mexico ‘New Spain’ and the buildings they encountered, some of which are visible in the above image:

‘They stood Westerly by common Consent, without keeping at a greater Distance from the Land than was necessary for their Safety, and discover’d on a Part of the Coast (which extended a great Way, and appeared very delightful) several Towns, with Buildings of Stone, which very much surprised them; and in the Confusion, with which they were all making their Observations, their Fancies represented them as great Cities, with Towers and Pinnacles; Objects at this Time, contrary to the ordinary Rule, appearing greater, as they were more distant. And because one of the Soldiers at that Time said, that this Country was like Spain, the Comparison so much pleased the Hearers, and made such an Impression upon them all, that we have no Account of any other Beginning of the Name of New Spain …’[39]

De Solís y Ribadeneyra spent a lot of time exploring the powerplay between Hernán Cortés and Diego Velázquez, and, as we have seen, he was keen to defend Cortés’ moral character. More importantly, however, he sheds light on Cortés’ initial interactions with Natives. He first met the Natives of Cozumel, with whom he made peace, and it was among them that he found Geronimo de Aguilar (1489-1531), who had been held captive by the Natives in the Yucatán. De Solís y Ribadeneyra describes their first encounter as follows: ‘Cortez caress’d him extremely; and covering him with the Coat he had on; informed himself in general who he was; and afterwards gave Orders to have him clothed, and regaled. He published it among his Soldiers, as a singular Felicity both to himself and the Undertaking, that he had redeemed a Christian from Slavery, having no other Motive in View at that Time than pure Charity’.[40]

From there, Cortés sailed to the territory of the Tabasco Indians, taking over their town by force, and making peace with their Cazique (chief). On their arrival at St. Juan de Ulva he was met by an embassy of Montezuma’s governors. De Solís y Ribadeneyra describes this important meeting as follows:

‘The Indians being admitted to the Presence of the General, acquainted him, That Pilpatoe and Teutile, the one Governor, and the other Captain-General of that Province, for the great Emperor Motezuma, had sent them to know of the Commander of that Fleet, with what Intention he was come upon their Coast; and to offer him what Succour and Assistance he should stand in need of, in order to continue his Voyage. Cortez caress’d them, gave them a few Baubles, and treated them with some Spanish Diet and Wine; and having thus obliged them, answer’d, “That he came as a Friend to treat concerning Matters of great Importance to their Prince, and all his Empire; for which Purpose he would meet the two Governors, and hoped to receive the same good Treatment from them, as others of his Nation had done the Year before.” And having receiv’d some Information concerning the Greatness of Motezuma, his Riches, and Form of Government, he sent them away very well contented’.[41]

Book II: Initial conquests

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), plate facing Book III, p. 50, ‘The Lake of Mexico and Parts Adjacent’.

At first, Cortés appeared to comply with the bureaucratic process suggested by the ambassadors but in practice he ignored Montezuma II’s requests and set about conquering Mexico. Montezuma II’s vacillation, coupled with predictions of his downfall which predated Cortes’ arrival, did little to help resistance to the Spanish invasion, factors noted by De Solís y Ribadeneyra: ‘Cortez’s persisting in his Resolution, gave much Trouble at Mexico. Motezuma was angry; and in his first Fury, proposed to make an End at once of those Strangers, who presumed to contend contrary to his Inclination. But afterwards, considering better, his Courage failed him, and Anger gave Way to Sorrow and Confusion.’[42]

Montezuma II (Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, more commonly known as Montezuma II, Emperor of Mexico, approximately 1480-1520) was not the only one with problems for Cortés faced challenges within his own ranks, particularly from those who wished to remain loyal to Velázquez. Eventually, a small band went back to Velázquez and the rest continued on with Cortés, accompanying him on a successful march through multiple territories, where they amassed several allies against Montezuma II. Their attempts to get rid of idols, build churches, and convert the Natives to Christianity were met with mixed responses, as can be seen in De Solís y Ribadeneyra’s account of Cortés’ destruction of the Zempoalans’ idols:

‘The Cazique immediately ordered his Masons to scrape the Walls, wiping out the Stains of human Blood. Which they preserved as an Ornament. After which they whiten’d them, laying on a Covering of that shining Mortar which they used in their Building; and they erected an Altar, on which was placed an Image of our Lady, with some ornamental Flowers and Lights; and the Day following, the holy Sacrifice of the Mass was celebrated with all possible Solemnity, in sight of abundance of Indians, who assisted at the Novelty, rather admiring than attentive; tho’ some bent their Knees, and endeavoured to imitate the Devotion of the Spaniards’.[43]

Cortés was not keen to highlight this rather lukewarm reception and instead emphasised in his letter to Charles V the success of his mission.[44] Indeed, Cortés could point to several successes: an attack by the Tlascalans had been repulsed and had led to a treaty of peace.[45] It is clear that this was a development which was not welcome to the Aztecs, for Montezuma II’s ambassadors did their best to undermine it, but the treaty held.[46]

Book III: Cortés enters Tenochtitlan

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), plate facing Book III, p. 70, ‘The City of Mexico’.

Books III and IV of De Solís y Ribadeneyra’s The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, mark the point in his narrative where Cortés began to face significant opposition from the tribes in the face of such an imminent threat, which began to coalesce around Montezuma II. The latter yet again attempted to undermine the peace which Cortés had made with Tlascala.[47] However, this mission was unsuccessful and the Spaniards moved on to the city of Cholula, where, following initial difficulties, they forced the Cholulans to make peace. As De Solís y Ribadeneyra remarks, Cortés was attempting to build his own network of alliances:

‘Cortez endeavour’d, before they returned, to reconcile the two Nations of Tlascala and Cholula. He set on foot a Treaty, removed the Difficulties, and, as his Authority was now well confirm’d with both Parties, he effected it in a few Days; and the Act of Confederacy and Alliance between the two Cities and their Districts, were celebrated with the Assistance of their Magistrates, and the accustomed Solemnities and Ceremonies’.[48]

Throughout the Spaniard’s journey, Montezuma II attempted to stop Cortés from progressing further into México but eventually he had no choice but to meet with him and though he tried to assert his authority Cortés made it clear that he had come (in his own words), ‘to free you from your Errors’.[49] After this encounter, Cortés was allowed entry to Montezuma II’s palace and into the city of México, Tenochtitlán.

De Solís y Ribadeneyra spends a lot of time describing the city, including the extravagance of Montezuma II’s palace, as well as the customs of the Mexican people, and in doing so, he provides his readers with a fascinating insight into the city itself. Perhaps one of the more impressive technological advancements within México City were the fountains:

‘The Conveniency of Fountains was very much increas’d in the Time of Motezuma; for the great Conduit, which conveys a Current of fresh Water to Mexico from the Mountain of Chapultepec, about a League distant from the City, was a Work of his; and by his Order and Contrivance a vast Cistern of Stone was made for a Reservatory; raising the same to such a Height as the Declivity for the Current requir’d: After this he gave Orders for a very thick Wall, with two open Canals made of Stone and Lime, of which one was always in Use, whenever the other requir’d cleaning: A Building extremely useful; and Motezuma valued himself so much upon the Invention, that he order’d his own Effigies and that of his Father, which bore a pretty near Resemblance to his, to be engrav’d on Two Stones, with an Ambition to perpetuate his Memory by so signal a Benefaction done to the City’.[50]

De Solís y Ribadeneyra concludes Book III with a climactic event: Cortés’s decision to imprison Montezuma II, and his execution of rebels.[51]

‘Cortez shut himself up with them, and they presently pleaded Guilty to all their Charges, acknowledging, That they had violated the Peace by their own Authority; had provok’d the Spaniards of Vera Cruz with their Hostilities, and had procur’d the Death of Arguillo, kill’d by their Order in cold Blood, tho’ a Prisoner of War. All this they confess’d without once mentioning that they had any Commission for so doing from Motezuma, till perceiving that the Punishment they had been threaten’d with was no Jest they endeavour’d to bring him in for an Accomplice, in order to save their Lives: But Cortez utterly refus’d to give Ear to that Evasion, treating it as a mere Chimera and Invention of theirs, merely to excuse themselves. They were judg’d by a Court Martial, and receiv’d Sentence of Death, with the Circumstance of having their Bodies publickly burn’d berfore the Royal Palace, as Criminals who had incurr’d the Penalty of High Treason’.[52]

Book IV: An Aztec emperor dies

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), frontispiece: Cortés meeting Montezuma II.

Cortés did not immediately execute Montezuma II, allowing him instead to be seen in public.[53] Possibly this was due to a debate among the Spaniards about whether they should overthrow Montezuma II or wait for a better time to do so. There was a rumour that Montezuma II’s nephew, the King of Tezeuco, was planning something seditious against the Spaniards, and Montezuma II was recorded as giving Cortés advice. De Solís y Ribadeneyra reports that ‘He was of Opinion that it would be best first to try gentle Means, and that the Dependance his Nephew had on him would easily bring him to Reason, by reminding him of the Obligations he lay under, and by inducing him to enter into an amicable Correspondence with the Spaniards’.[54] This piece of advice gained Montezuma II respect from Cortés.

Furthermore, Montezuma II formally announced that the King of Spain would be acknowledged as his successor, and as such, should be obeyed and given tribute. In this way he hoped to get Cortés out of México: ‘This was his Proposal, and in this he granted at once every Thing that he thought the Spaniards could have the Boldness to desire; satisfying both their Ambition and Avarice, in order to deprive them of all Pretence for remaining longer in his Court’.[55] Following this announcement, gold and jewels were given to Cortés, and Montezuma II urged him to depart for Spain.[56] This plan was, however, delayed when Diego Velázquez and his fleet of ships led by Pamphilo de Narvaez (1478-1528) appeared off the coast of México, coming for Cortés. As a result of this, Cortés was forced to leave Montezuma II and some of his troops behind to deal with Narvaez. Cortés attempted to make peace with Narvaez on multiple occasions, but to no avail.[57] He then imprisoned Narvaez and, as De Solís y Ribadeneyra notes, in his success ‘Cortez found himself posses’d of an Army of more than a Thousand Spaniards, the only Enemies who could give him Umbrage, safe in his Custody, a Fleet of Eleven Ships and Seven Brigantines at his Disposal, the last Effort of Diego Velasquez overthrown and brought to nought, Master of sufficient Force to return to his principal Conquest’.[58] However, this moment of success was short-lived because Cortés received news that the Mexicans had risen against the Spaniards. De Solís y Ribadeneyra had his own views on their motivations:

‘Some have affirm’d the Source of Sedition to have proceeded from the Loyalty and Fidelity of the Mexicans; reporting, that their sole Reason for taking up Arms, was in order to rescue their Soveraign from the Opression he lay under; a Sentiment, which comes nearer to Reason and Probability, than it does to real Fact. Others attribute this Rupture to the Zeal of the Indian Sacerdotes: And this Opinion indeed has some Appearance of Truth’.[59]

Cortés quickly returned, and in the ensuing conflict, Montezuma II was killed, an event which led to a massive outcry by his subjects. As De Solís y Ribadeneyra recounts, following the official announcement of his death: ‘The Outcries and Clamours of the People, who throng’d up and down in Swarms, lasted the whole Night; repeating thro’ every Street the Name of Motezuma, with turbulent Uneasiness mix’d with Sorrow, which tho’ it express’d a Sort of relenting Reflection, yet still carry’d the same Face of Sedition as before’.[60]

Montezuma II’s death did not scotch the Aztec counter-attack, and eventually Cortés had to retreat to the town of Tacuba. From there, the Spaniards marched towards Tlascala while being pursued by the Mexicans.[61] Clearly the situation was precarious for De Solís y Ribadeneyra tells his readers that ‘Cortez began to examine the Countenances of his People with that natural Alacrity which influenc’d their Hearts far better than Words; and finding them inspir’d, rather with a Martial and generous Resentment than with Fear and Consternation, “Our Case is now such, said he, that we must either die or conquer: The Cause of our God fight for us”’.[62] Eventually, they defeated the Mexicans after several retreats in the valley of Otumba. De Solís y Ribadeneyra remarks that, ‘All Writers, as well Strangers as those of our own Nation, relate this Victory as one of the greatest that was obtain’d in the Two America’s. And if it were certain, that Santiago, or St. James the Apostle, fought visibly for his Spaniard’.[63] The odds were against the Spaniards, but somehow they were victorious.

Book V: Consolidation of Cortés’ Rule

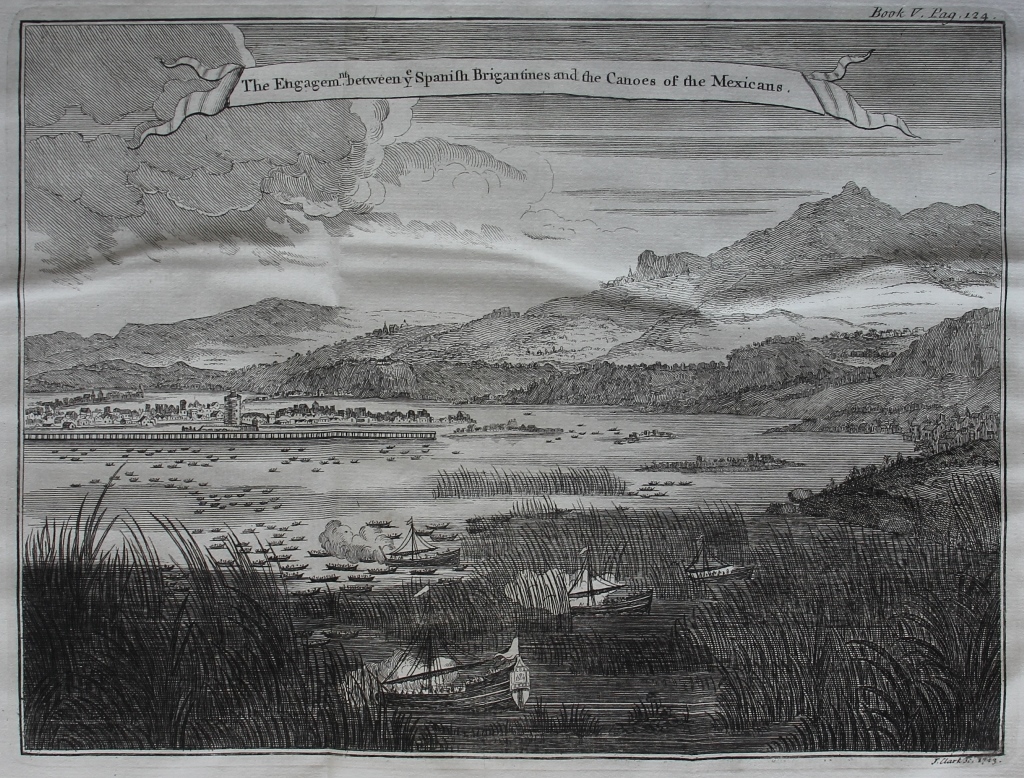

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), plate facing Book V, p. 124, ‘The Engagement between ye Spanish Brigantines and the Canoes of the Mexicans’.

At this point in the conflict, with Montezuma II dead and the rebels subdued, De Solís y Ribadeneyra begins to describe the downfall of the Native forces, including the quashing of a number of smaller rebellions in Tepeaca and Guacachula. This, however, was not something that was fully supported by all of the members in Cortés’ party, for De Solís y Ribadeneyra tells us that ‘Cortez was employ’d in convincing his own People, of the Necessity they lay under of chastizing the Indians of Tepeaca; representing to them, the Rebellion of those Traytors, and the Death of so many Spaniards; with what other Motives could incite them to Compassion and Revenge. But they did not all agree in the Necessity of this Expedition, and more especially, the Troops of Narbaez very strenuously oppos’d it’.[64] Unexpectedly, Cortés received a reinforcement of Spaniards as well as ammunition that allowed him to march on the city of Tezeuco.[65] At Tezeuco, he restored the kingdom to a lawful successor who had been baptized: ‘the Ceremony of which was performed publickly, and with great solemnity, the Prince desiring to take the name of Don Hernando Cortez, in respect to his Godfather’.[66] After this, Cortés and his troops began to march towards Iztapalapa.[67]

In much of Book V De Solís y Ribadeneyra describes Cortés’ forays against the Mexican resistance and his journey further into the land of México. While pursuing the Mexicans, Cortés learned of a plot against him by the Spaniards accompanying him, and quickly punished them by killing the Spanish soldier who led the conspiracy.[68] The Spaniards were not the only ones plotting against him, for during this time, he also discovered a seditious plot by the Tlascalans, to which he responded by calling for the death of Xicotencal (1425-1522):

‘Hernan Cortez, who was presently informed of it by the Tlascalans themselves, was much concerned at a Behaviour of such dangerous Consequence, of so considerable a Commander among those Nations, at a time when he was just ready to put his Designs in execution. He sent some noble Indians of Tezeuco after him, to persuade him to return, or at least to stay till he had heard what he had to offer; but the Answer of Xicotencal, (which was not only resolute, but discourteous, and with Contempt) so provoked Cortez, that he immediately sent three Companies of Spaniards, with additional Force of Tezeucan Indians and Chalqueses, with Orders to take him Prisoner, or kill him in case of Resistance’.[69]

The pursuit of the Mexicans came to a boiling point when Cortés and his ships attacked a fleet of Mexican canoes. De Solís y Ribadeneyra provides a graphic account: ‘Cortez put five and twenty Spaniards on board each Vessel, under the Command of a Capitain, with twelve Rowers, fix on each Side, and one Piece of Artilllery.’[70] Though Cortés was initially defeated by the Mexicans and forced to retreat, he later returned to the lake and, following his imprisonment of Cuauhtemoc, Emperor of Mexico, (1495?-1525) (Guatimozin), the last Aztec emperor, the city surrendered.[71] It is at this point that Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra ends his history of the conquest of Mexico.

Antonio de Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), plate facing Book V, p. 146, ‘Guatimozin taken in his Retreat by Holguin’.

Conclusion

The conquest of Mexico was a series of strategic takeovers led by Hernán Cortés against Montezuma II’s empire. Feeding off of inter-tribal conflicts and old grudges held by the various tribes in México against the Aztecs, Cortés was able to defeat the Aztecs and successfully colonize México in the name of the Crown of Spain. However, as De Solís y Ribadeneyra demonstrates in his book The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, this journey to colonize and settle México was not without its challenges. Hernán Cortés had to deal with plots against him not only from the Natives but also from the Spaniards within his company. Furthermore, he had to fight for his right to colonize México in the Spanish court against Diego Velázquez, his previous superior. This journey is something that would have attracted the interest of many at the time, and that of later readers such as Edward Worth (1676-1733), as this history encouraged people in Europe to reflect on the moral implications of colonization, as well as the place of the New World within the context of Christian beliefs.

Text: Ms Cera Linnell, MA Student, Public History, University College of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Sources

Cortés, Hernán, Letters from Mexico, translated, edited and with a new introduction by Anthony Pagden, with an introductory essay by J. H. Elliott (New Haven, Conn. and London, 2001).

Chipman, ‘Donald E., Antonio de Solís, cronista indiano; estudio sobre las formas historiográficas del Barroco. By Luis A. Arocena. Buenos Aires, 1963. Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires. Notes. Illustrations. Bibliography. Index. Pp. 526. Paper’, Hispanic American Historical Review, 44, no. 4 (1964), 605-607 [Book Review].

Gibney, John, ‘Rycaut, Sir Paul’, Dictionary of Irish Biography.

Hanke, Lewis, The Spanish struggle for justice in the conquest of America (Philadelphia, Pa., 1949).

Innes, Ralph Hammond, ‘Hernán Cortés’, Encyclopædia Britannica.

Schmal, John, ‘The Indigenous People of Central Mexico: 1111 to 1521’, Indigenous Mexico.

Solís y Ribadeneyra, Antonio de, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724).

University of Notre Dame, Rare Books & Special Collections, ‘Garcilaso Inca de La Vega (1539-1616)’, Selections from the Library of José Durand : Purchased through the gift of the Tom and Dottie Corson Family [Online Exhibition].

[1] Worth’s English translation uses the English spelling ‘Hernan Cortez’.

[2] Cortés, Hernán, Letters from Mexico, translated, edited and with a new introduction by Anthony Pagden, with an introductory essay by J. H. Elliott (New Haven, Conn. and London, 2001), p. xv.

[3] Hanke, Lewis, The Spanish struggle for justice in the conquest of America (Philadelphia, Pa., 1949), pp 27-29.

[4] Innes, Ralph Hammond, ‘Later Years of Hernán Cortés’, in ‘Hernán Cortés’, Encyclopædia Britannica.

[5] Chipman, Donald E., ‘Antonio de Solís, cronista indiano; estudio sobre las formas historiográficas del Barroco. By Luis A. Arocena. Buenos Aires, 1963. Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires. Notes. Illustrations. Bibliography. Index. Pp. 526. Paper’, Hispanic American Historical Review, 44, no. 4 (1964), 605 [Book Review].

[6] Ibid.

[7] Solís y Ribadeneyra, Antonio de, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. Done into English from the original Spanish of Don Antonio de Solis … By Thomas Townsend Esq. (London, 1724), Sig. [b]1r.

[8] Ibid., Sig. [b]1v.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Gibney, John, ‘Rycaut, Sir Paul’, Dictionary of Irish Biography.

[11] Innes, ‘Hernán Cortés’, Encyclopædia Britannica.

[12] Solís y Ribadeneyra, The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, Book I, p. 13.

[13] Innes, ‘Hernán Cortés’, Encyclopædia Britannica.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Cortés, Letters from Mexico, p. xii.

[16] Ibid., p. xiii.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Solís y Ribadeneyra, The history of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, Book I, p. 26.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., Book I, p. 27.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Innes, ‘Later Years of Hernán Cortés’, in ‘Hernán Cortés’, Encyclopædia Britannica.

[24] Solís y Ribadeneyra, The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, Book I, p. 32.

[25] Cortés, Letters from Mexico, pp xiii-xiv.

[26] Ibid., p. xiv.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid., p. xv.

[30] Schmal, John, ‘The Indigenous People of Central Mexico: 1111 to 1521’, Indigenous Mexico.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Solís y Ribadeneyra, The History of the Conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards, Book I, p. 4.

[38] Ibid., Book I, p. 13.

[39] Ibid., Book I, p. 15.

[40] Ibid., Book I, p. 49.

[41] Ibid., Book I, p. 69.

[42] Ibid., Book II, pp 79; 83-84.

[43] Ibid., Book II, pp 118-119.

[44] Ibid., Book II, pp 120-121.

[45] Ibid., Book II, p. 140.

[46] Ibid., Book II, p. 160.

[47] Ibid., Book III, p. 9.

[48] Ibid., Book III, p. 43.

[49] Ibid., Book III, pp 62-63.

[50] Ibid., Book III, p. 78.

[51] Ibid., Book III, p. 104.

[52] Ibid., Book III, p. 114.

[53] Ibid., Book IV, p. 119.

[54] Ibid., Book IV, p. 130.

[55] Ibid., Book IV, p. 134.

[56] Ibid., Book IV, p. 141.

[57] Ibid., Book IV, p. 182.

[58] Ibid., Book IV, p. 185.

[59] Ibid., Book IV, p. 194.

[60] Ibid., Book IV, p. 215.

[61] Ibid., Book IV, p. 238.

[62] Ibid., Book IV, p. 249.

[63] Ibid., Book IV, pp 251-252.

[64] Ibid., Book V, pp 12-13.

[65] Ibid., Book V, p. 26.

[66] Ibid., Book V, p. 67.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Ibid., Book V, p. 108.

[69] Ibid., Book V, p. 110.

[70] Ibid., Book V, p. 112.

[71] Ibid., Book V, p. 150.