Thomas Ross and The Second Punic War between Hannibal, and the Romanes (London, 1661)

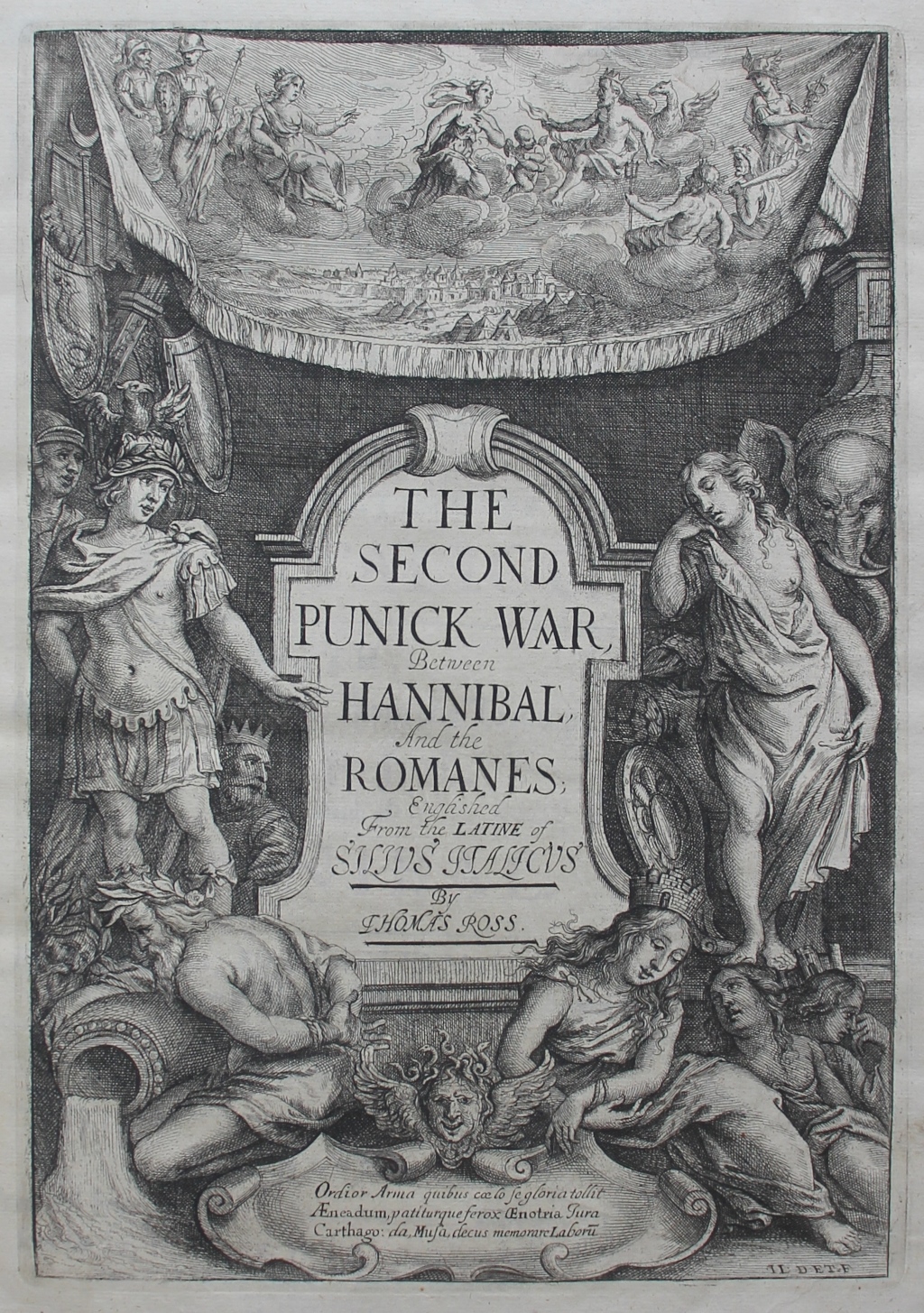

Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), engraved title page.

The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes was a translation into English by Thomas Ross (bap. 1620, d. 1675), of an epic poem written by Tiberius Catius Asconius Silius Italicus (25–101 A.D.). It was first published in 1661, then republished in 1672 with minor differences in layout. The 1661 edition was printed by Thomas Roycroft (1651–77), a seventeenth-century London printer who produced copious amounts of books, most prominently the Polygott Bible, which has six folio volumes.[1] Roycroft was given a share in the King’s Printing House and assigned as his Oriental language printer upon the king’s coronation.[2] Unfortunately, the Fire of London destroyed his printing house, which resulted in the destruction of numerous priceless books. He eventually rose to the position of Master of the Stationer’s Company in 1675.[3] Roycroft eventually passed away on 10 August 1677.[4]

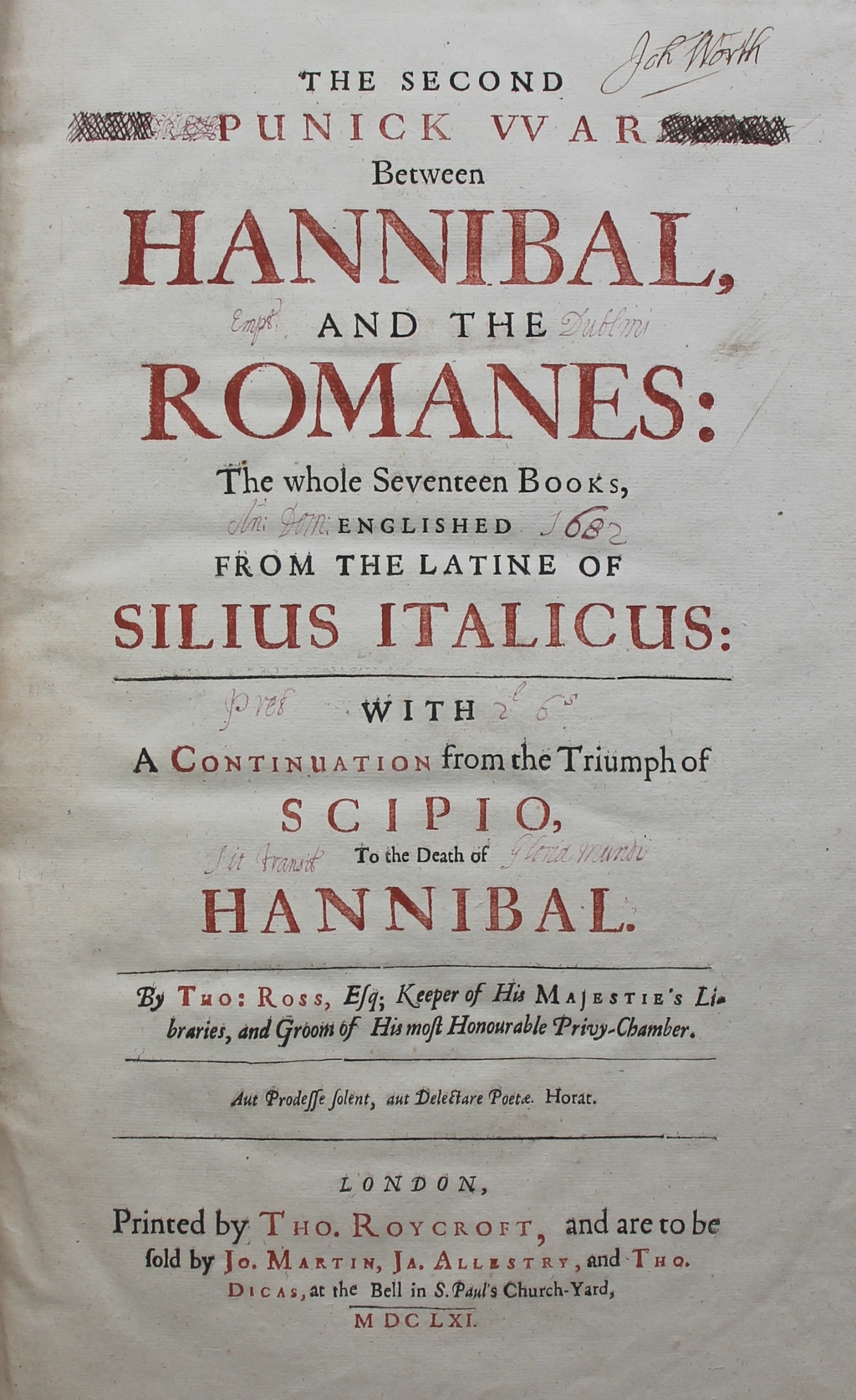

Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), title page with annotations by John Worth (1648–88).

There were three booksellers mentioned on the title page of The second Punick war: one of whom was James Allestry (d. 1670), who was first mentioned as a bookseller at London in accounts dating to 1652. Thus, not much is known about his early years.[5] He began working with two other English booksellers, Thomas Dicas (d. 1669) and John Martin (1649–80), and Allestry’s employment took place at the Bell in St Paul’s Churchyard in 1660.[6] One of the most important capitalists in book trading at the time, Allestry was named the Royal Society’s bookseller and publisher in the same year.[7] His shop was the hub of a great deal of wealth and knowledge, which was maintained in collaboration with Dicas and Martin. Following Allestry’s passing, Martin assumed Allestry’s role as the Royal Society publisher.[8]

The volume has twenty-two different engravings placed throughout the text.[9] These were the work of Jozef Lamorlet (1626–c. 1681), an engraver based in Antwerp. His signature, located in the engraved title page’s lower right corner, alerts us to his intention to claim authorship. In shortened form, it says, ‘J.L. delineavit et fecit’.[10] Throughout the book, there are others that are inscribed with the words, ‘J.L. fecit’ (plates 1, 6, 10, 12, and 14) and ‘J.L. invenit et fecit’ (plates, 2, 3, 11, 13, 15, 17, 18 and 20).[11] Since ‘invenire’ means inventor in English, ‘delineare’ means designer, and ‘facere’ means maker, the Latin terms used here help us understand his understanding of his role, which in turn provides us with a glimpse into Lamorlet’s identity as an engraver.[12]

We know that Edward Worth (1676–1733), inherited the earlier 1661 edition from his father, John Worth (1648–88), Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, for the latter signed his name on the title page of the work. Worth Senior also provided information about when and where he bought the book (Dublin, 1682), and its price (£2 and 6 shillings). As you can see from the above image, John Worth also added a comment (an unusual practice for him): ‘Sic transit gloria mundi’ (thus passes the glory of the world). The phrase was appropriate, for Silius Italicus’ epic poem certainly demonstrated the transitory nature of success.

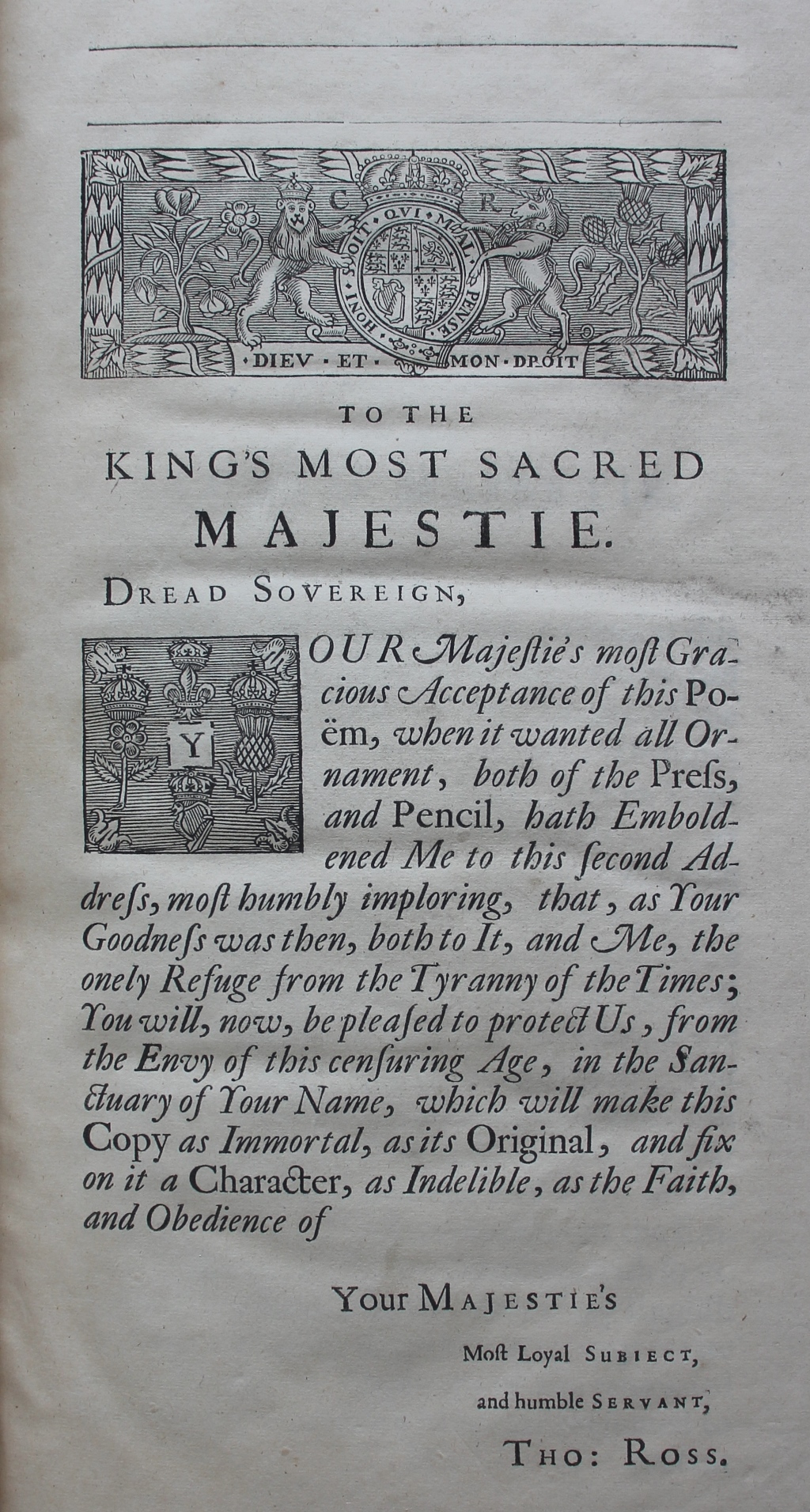

Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), Sig. B1r. Dedication to Charles II.

The translator, Thomas Ross, a courtier and librarian, was born in 1620 and died in 1675.[13] Educated at Charter House and Christ’s College, Cambridge, he earned his B.A. in 1642 and was the first English translator of several works of Imperial Roman literature, including The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes.[14] Ross’ translation of this famous classical Latin epic poem remains one of the best known, for his translation of the Punica made history in terms of its length (it is c. 12,000 lines long).[15] Indeed, Ross provided his readers with a continuation of Silius Italicus’ epic, continuing the story up to Hannibal’s death. His version of the Punica, which was dedicated to Charles II (1630–85), King of England, Scotland and Ireland, provides an illuminating example of how classical literature was used by a courtier in competition for royal favour.[16]

After Thomas Ross completed much of his schooling, he was involved in many dastardly plots, one of which was evidently a plot to assassinate Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), lord protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland.[17] In 1658, he was appointed as the official tutor to James Scott (1649–85), later Duke of Monmouth and first duke of Buccleuch, who was around 9 years old, and going by the name of ‘Mr. Crofts’.[18] Ross appears to have left his position in order to become Keeper of the King’s Library. Some thought his departure was for another reason – James II and VII (1633–1701), King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, accused him in his memoirs of playing a role in what later became known as the ‘black box’ affair, which, as Lewin notes, led to accusations that Ross had, in 1658, proposed that Dr John Cosin (1595–1672), who later became the Bishop of Durham in 1660, should declare that a marriage had taken place between Charles II and Lucy Walters (1630?–58), the mother of James Scott.[19]

David Loggan, Portrait of James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, nearly half length in an oval on a pedestal, long hair, collar, sash, and coat (c. 1670–80). Engraving. Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Bond argues that James II’s interpretation of events is flawed for Ross continued to receive patronage from Charles II.[20] Ross, as the tutor to the Duke of Monmouth, never openly stated that he hoped or expected his pupil would become king.[21] There is no doubt, however, that his anonymous writings which he directly dedicated to Monmouth were meant to be read as ‘mirrors for princes’.[22] Bond suggests that some of these texts may have inspired Monmouth’s later rebellious actions but Ross was always careful to protect himself. As Bond notes, he was ‘scrupulous to avoid the direct suggestion that Monmouth must be trained to rule. Ross likewise tiptoes away from any hint of treason’.[23] In this stratagem he was successful, for by 1666 he was appointed secretary to Henry Coventry (1617/18–86), English ambassador to Sweden. The following year he married Mary Mintern (bap. 1620, d. in or after 1675) and three years later, in 1675, he died at Westminster.[24]

Ross’ dedication of his translation to King Charles II, give us some clues as to his motivation for translating the Punica: he clearly wanted to earn the king’s favour so that he could become a well-known poet. There can be little doubt that Ross’ intention was to improve his standing with Charles II, with whom he had served in exile.[25] In order to make his mark, he decided to move away from the well-known literary giants, Virgil and Homer, and instead decided to translate a copy of the lesser-known Silius Italicus’ Punica.[26] Ross’ version of the Punica was thus designed to make him stand out among Charles’ literary coterie.[27] In many ways, Ross’ limited talents were rather well-suited to translating the Punica into English.[28] As Bond notes, his translation of the Punica omits any discussion of the literary merits of the work and he provides his readers with no information about his theory of translation.[29]

Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), Sig. A2v. Portrait of Charles II.

There were themes in the poem which Ross might well have thought relevant to Charles II. The Civil Wars in England had left the Royalist side in such a precarious position that many at the time thought it might share the fate of Carthage, and few could hope that it would emerge, like Rome and its empire, victorious. Though the translation was printed in 1661, the work included, ‘The Epistle at Bruges’, which was a dedication to Charles II, dated 18 November 1657, while the king was still in exile. In it Ross declared that his intention in translating the work was because, ‘by reflecting on them, Your Majesty may see what imperishable Monuments Great Persons may build to themselves, in asserting their Country; and, that as Your Sacred Person is endowed with all those Virtues, that rendred the Valiant HANNIBAL famous, or SCIPIO a Conqueror: so, by the blessing of Heaven on Your Majestie’s Designs, some happy Pen may have Matter to build you such another Monument for future Times’.[30] Ross’ decision to translate the relatively obscure text of the Punica was because it offered him two distinct scenarios of what could happen to the Royalists in England.[31] For Ross, Charles II could be thought to be either a Scipio or a Hannibal.[32]. Happily for Ross, Charles II prevailed and Ross could reflect this in the stanza written to accompany the image above: ‘Could Hannibal, and Scipio, in whom all the vast hopes of Carthage, and of Rome, Were fix’d, Revive, and see how easily You could By Your Sole Virtue, Kingdoms can Subdue; How from the Rage of War, without the Stain of Blood, Your Sacred Crowns, and Triumphs gain: there would be no more contend, who best might claim Priority; but yield it to Your Name, Rome would her Gen’ral, Carthage Hers refuse, And jointly You the World’s Commander chuse’.[33] This quotation could be read in multiple ways but Ross might well have thought it applicable to Charles II who, despite reverses at the Battle of Worcester, had gone on to regain the crown and become (in Ross’ eyes), ‘the World’s Commander’.[34]

Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), Book XV, plate 15 facing p. 419.

Silius Italicus is best-known for writing his 17-book depiction of the Second Punic War. His birthplace is unknown, but what is believed is that he came from the town of Italica in Spain. Whether Silius committed his philosophic dialogues and speeches to writing or not, is hard to say. His only preserved work is the poem, which is the longest preserved poem in classical Latin literature. The poem takes Virgil as its main stylistic and dramatic inspiration and indeed could be viewed as a companion piece to the Aeneid since it begins by discussing the reasons for Juno’s anger against Rome (due principally to Aeneas’ treatment of Dido of Carthage). However, Silius is not wholly dependent on Virgil and provides his readers with a multitude of characters, each of whom may reflect different philosophical positions. Of these, the most important is Stoicism. Though Silius Italicus’ verse are not covered in Stoic gloom like those of Lucan, there are clear Stoic echoes throughout the poem. Silius was but one of numerous Romans of the Early Roman Empire who had the courage to stand up for their own opinions.

Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), Book IV, plate 4 facing p. 87.

Interest in Silius mostly vanished during the nineteenth century. More recently, classical scholars have renewed interest in these later imperial epics, and they have turned to Silius’ poetry. In this way, the Punica helped Latin poetry stay alive and is an important source for anyone interested in studying late imperial perspectives on the Roman Republic. It is also a crucial text for students of Flavian writings and is still regularly translated in many Latin classrooms. Whilst very little may be known about Silius, his writing is still extremely influential and necessary, as it shows us the rise and fall of the Carthaginian empire. In addition to its political significance, Ross’ translation of Silius’ work is noteworthy from bibliographical, artistic, and literary-historical perspectives.[35]

Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), Book VII, plate 7 facing p. 181.

Text: Mr William Gawtry, Third Year Student, Classical Civilizations and Communication & Digital Studies, University of Mary Washington, Fredericksburg, VA, USA.

Sources:

Augoustakis, Antony, ‘Thomas Ross’ Translation and Continuation of Silius Italicus’ Punica in the English Restoration’, in Robert C. Simms (ed.), Brill’s Companion to Prequels, Sequels, and Retellings of Classical Epic (Leiden, 2018), pp 335–356.

Bond, Christopher, ‘The Phœnix and the Prince: The Poetry of Thomas Ross and Literary Culture in the Court of Charles II’, The Review of English Studies, 60, no. 246 (2009), 588–604.

Daemen-de Gelder, Katrien, and Jean-Pierre Vander Motten, ‘Thomas Ross’s Second Punick War (London 1661 and 1672): Royalist Panegyric and Artistic Collaboration in the Southern Netherlands’, Quaerendo, 38, no. 1 (2008), 32–48.

Lewin, Philip, ‘Thomas Ross (bap. 1620, d. 1675), courtier and librarian’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Livius, Titus, and Aubrey Selincourt (tr.), The War with Hannibal (New York City, NY, 1965).

Plomer, Henry R., A Dictionary of the Booksellers and Printers who were at work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1641 to 1667 (London, 1907).

Silius Italicus, Tiberius Catius, and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661).

[1] Plomer, Henry R., A Dictionary of the Booksellers and Printers who were at work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1641 to 1667 (London, 1907), p. 158.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p. 2.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, p. 123.

[9] Daemen-de Gelder, Katrien, and Jean-Pierre Vander Motten, ‘Thomas Ross’s Second Punick War (London 1661 and 1672): Royalist Panegyric and Artistic Collaboration in the Southern Netherlands’, Quaerendo, 38, no. 1 (2008), 40.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., 41.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Bond, Christopher, ‘The Phœnix and the Prince: The Poetry of Thomas Ross and Literary Culture in the Court of Charles II’, The Review of English Studies, 60, no. 246 (2009), 588.

[14] Ibid., 589.

[15] Ibid., 590.

[16] Ibid., 588.

[17] Ibid., 589.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Lewin, Philip, ‘Thomas Ross (bap. 1620, d. 1675), courtier and librarian’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[20] Bond, ‘The Phœnix and the Prince’, 590.

[21] Ibid., 596.

[22] Ibid., 604.

[23] Ibid., 599 and 597.

[24] Ibid., 589.

[25] Ibid., 595.

[26] Ibid., 590.

[27] Ibid., 594.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid., 595.

[30] Silius Italicus, Tiberius Catius, and Thomas Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes : the whole seventeen books, Englished from the Latine of Silius Italicus ; with a continuation from the triumph of Scipio, to the death of Hannibal … (London, 1661), Sig. B2v.

[31] Augoustakis, Antony, ‘Thomas Ross’ Translation and Continuation of Silius Italicus’ Punica in the English Restoration’, in Robert C. Simms (ed.), Brill’s Companion to Prequels, Sequels, and Retellings of Classical Epic (Leiden, 2018), pp 335–356, 338.

[32] Ibid., 339.

[33] Silius Italicus and Ross (tr.), The second Punick war between Hannibal, and the Romanes, Sig. A2v.

[34] Bond, ‘The Phœnix and the Prince’, 589.

[35] Daemen-de Gelder and Vander Motten, ‘Thomas Ross’s Second Punick War (London 1661 and 1672)’, 36.