Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois … (Amsterdam, 1717), by Pierre Daniel Huet.

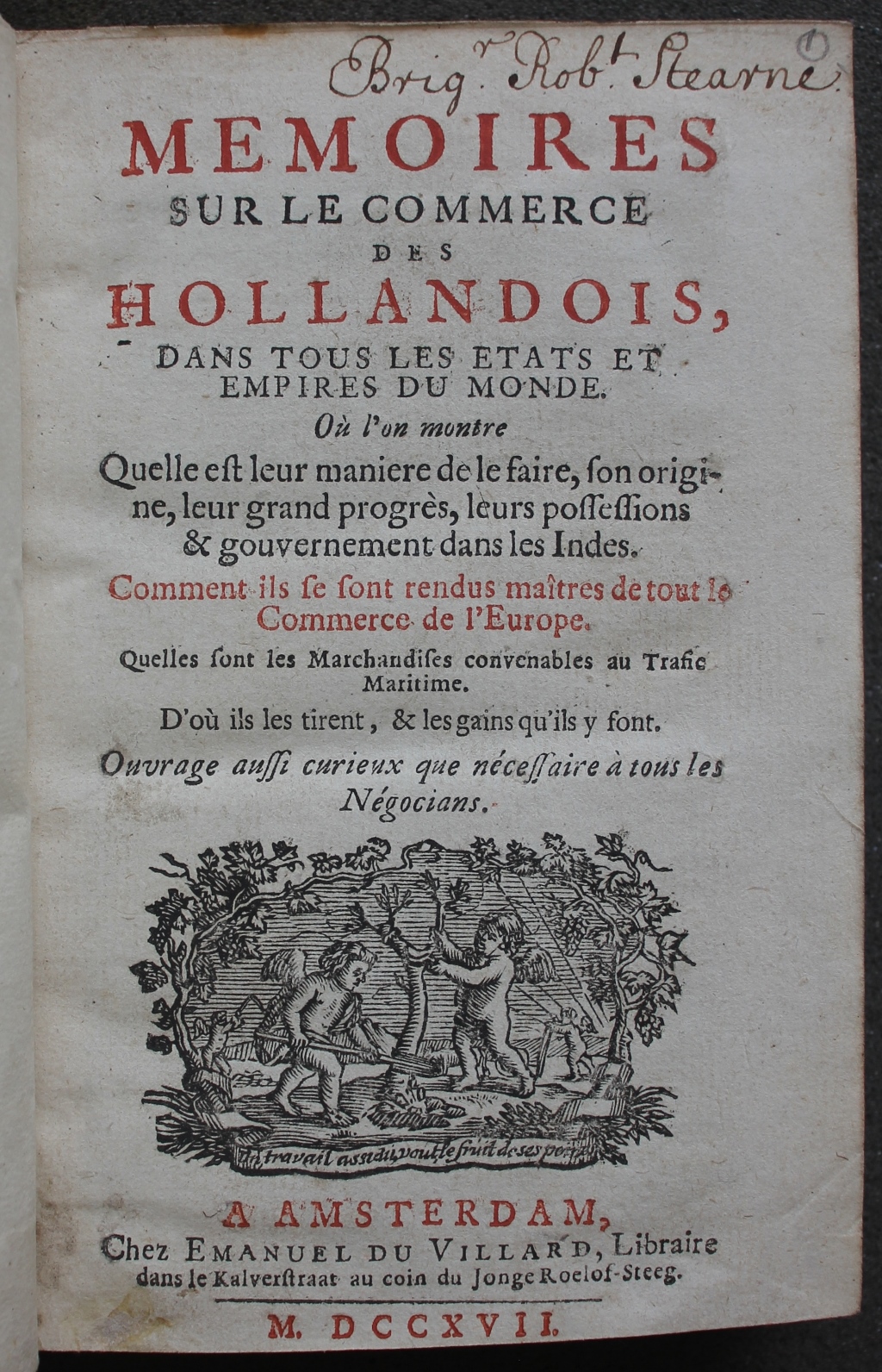

Pierre Daniel Huet, Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois … (Amsterdam, 1717), title page.

Edward Worth’s edition of Pierre Daniel Huet’s Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois was published by Emmanuel Du Villard in 1717 at Amsterdam, and sold in his shop in the Kalverstraat at the corner of Jonge Roelof Steeg. Both the author and publisher were French: Emmanuel Du Villard (1693–1776), often referred to as a Genevan, was of Huguenot descent — a term for French Protestants in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. He was likely a descendant of Protestants who had fled France following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 by King Louis XIV (1628–1715), which had previously protected the Huguenots.

Evidently Du Villard’s firm prospered: around 1718, he employed another Huguenot as an apprentice, François Changuion (1694–1777), and by 1719, the two were considered business partners and officially changed the name of the company to Du Villard et Changuion. In 1721, after Du Villard took the position of libraire du Collège de Genève, François took over the company, and it was run by him and his son until the early nineteenth century. The firm produced a number of notable works, including Discours sur la polysynodie (Amsterdam, 1719) by Charles Irénée Castel de Saint Pierre (1658–1743), which argued that the plural council system was the most advantageous form of ministry for a King and his kingdom. They were also responsible for an even more important work: Pierre Des Maizeaux’s Recueil de diverses pieces sur la Philosophie, La Religion Naturelle, l’Histoire, les Mathématiques, &c. Par Mrs. Leibniz, Clarke, Newton & autres Auteurs célèbres (Amsterdam, 1720).[1] This text, including as it did letters between Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) and Samuel Clarke (1675–1729) concerning the calculus dispute between Newton and Leibniz, was likewise collected by Worth.

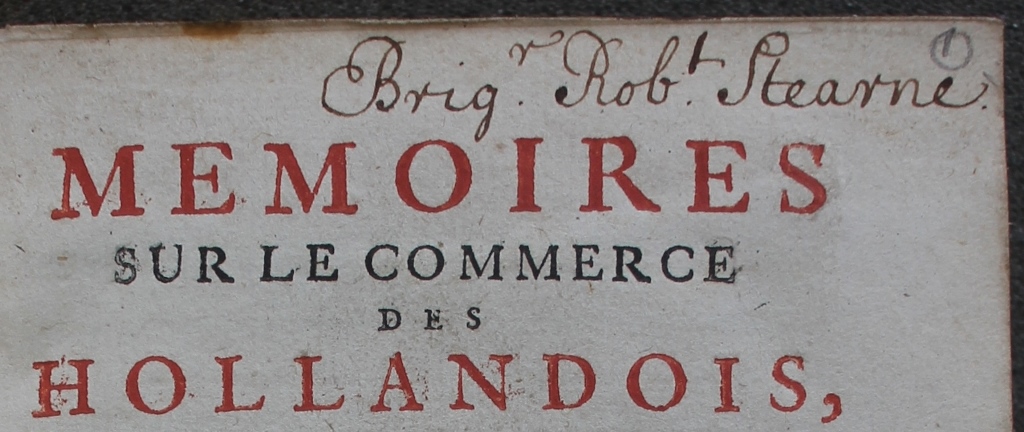

Pierre Daniel Huet, Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois … (Amsterdam, 1717), title page detail.

Worth clearly did not buy his copy of Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois hot off the press because his copy bears a provenance mark on the title page which points to a previous owner: ‘Brig. Rob. Stearne’. This refers to Brigadier Robert Stearne (1658–1732), an officer in the Royal Irish Regiment. Over his 40 years of service (1678–1717), Stearne participated in numerous significant battles and sieges, including: Boyne (1690), Limerick (1690 & 91), Athlone (1691), Aughrim (1691), Namur (1695), Schellenburg (1704), Blenheim (1704), Ramillies (1706), Menin (1706), Oudenarde (1708), Lille (1708), Tournai (1709), and Bouchain (1711), all of which he survived. Stearne achieved the rank of Brigadier General after 33 years of service in 1711 and was appointed Major General nine years later. After leaving the regiment in 1717, he served as Governor of Duncannon Fort, and in 1728, he became the Governor of the Royal Military Hospital in Kilmainham (now the Irish Museum of Modern Art, located just ±750 metres from the Edward Worth Library). Stearne passed away in 1732. His life story is documented in his personal journal, now housed in the National Library of Ireland, along with his death will and marriage records from the dioceses of Cork and Ross.[2]

Portrait of Pierre Daniel Huet (1630–1721). Print by Gerard Edelinck, after a painting by Nicolas de Largillière. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Pierre Daniel Huet (1630–1721), the author of this book, was a bishop and a scholar of science and literature, born in Caen, France. Educated in the Jesuit tradition, Huet is remembered today as a prominent figure in the seventeenth-century Republic of Letters — a dynamic, organic network of European intellectuals united by a shared neo-Latin culture, a deep appreciation for classical works, and a pursuit of high moral and intellectual ideals. It thrived solely through the active collaboration and contributions of its members. Huet was prolific and his other works include: translations of Origen’s biblical commentaries (1666), two works of Christian apologetics – Demonstratio Evangelica (Paris, 1679) and Alnetanae Quaestiones (Paris, 1690), as well as a tract on the origins of the novel, Traitté de l’origine des romans (Paris, 1670). Although not all of Huet’s writings were in Latin, they consistently reflected a strong classical spirit. By the eighteenth century — a period of intellectual transformation — Huet’s work, while still respected, was increasingly seen as old-fashioned. The new generation of scholars favoured a more democratic style of writing, using everyday language (vernacular) to make knowledge accessible to a broader audience. In addition to his literary contributions, Huet was also one of the founders of the Académie de Physique in Caen and served as the bishop of Avranches in the late 1680s.[3]

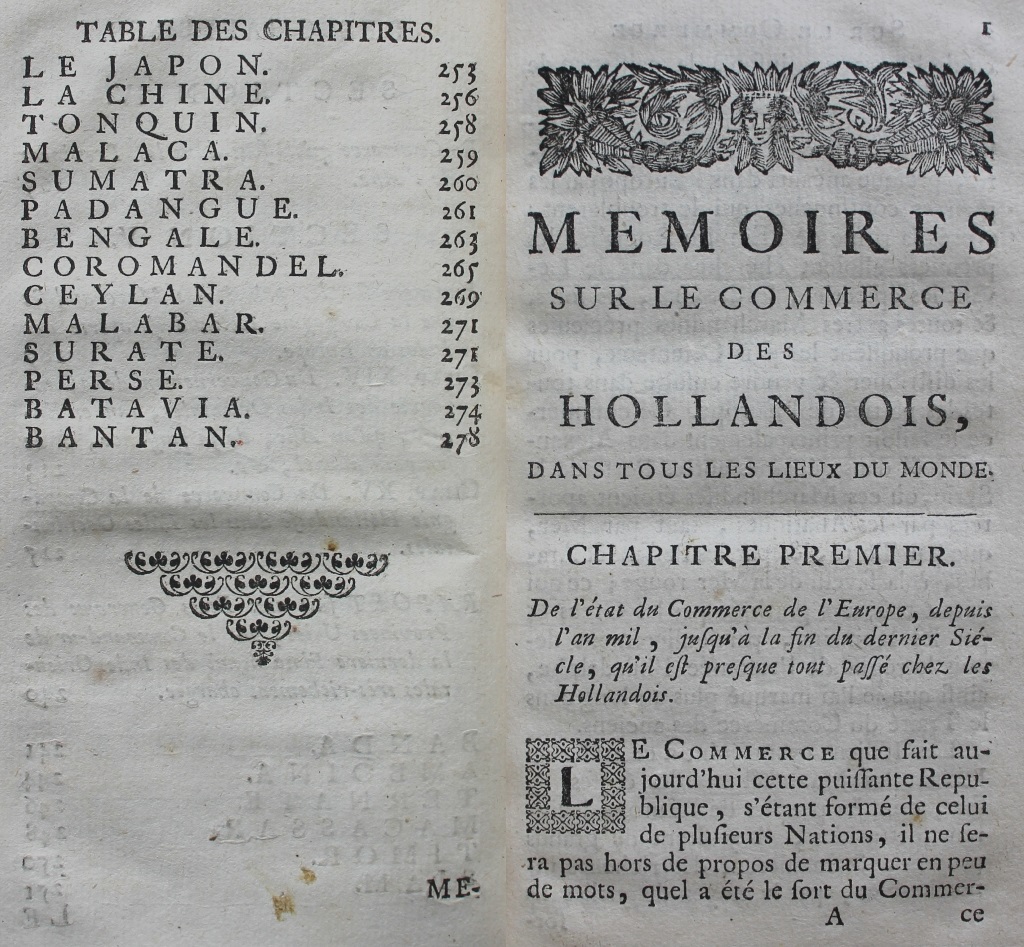

Pierre Daniel Huet, Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois … (Amsterdam, 1717), Sig. *12v and p. 1. Contents list.

Mémoires sur le Commerce des Hollandois opens with an introduction, an unusual table of contents, and then proceeds to the main text. The book itself consists of 15 chapters, organized into 5 sections. It provides a concise overview of trade conditions in 20 regions of Asia, 10 of which are located in the East Indies. However, it is important to note that the arrangement of chapters and sections is not linear; instead, it follows a flexible thematic structure, where one section does not necessarily build directly upon the previous one. The book opens with a foreword in which Huet explains that his motivation for writing came from a request by ‘Some Persons of Honour and Distinction’, who sought a better understanding of the relationship between trade and state politics — an issue still poorly understood in France at the time.[4] He chose to focus on Dutch trade, which was considered the most prominent among European nations. Huet referred to this work as ‘a sufficient proof’ of his efforts, noting that in order to complete it, he proudly sacrificed considerable time, energy, and money, travelling through various regions of Europe and consulting with experts in the field.[5]

Chapters 1-3 focus on the background of the momentum behind the rise of the Netherlands as a new power in global trade, driven by unfavourable conditions in other trading cities due to war, high taxes, and political and religious conflicts. It begins by examining how Flanders, in the tenth century, with its two major trading cities — Ghent and Bruges — became the catalyst for the revival of European trade after the Dark Ages. This was followed by Venice in Italy in the subsequent century. Germany, represented by the Hanseatic League, flourished in the late twelfth century, until the world exploration by the Portuguese and Spanish (late fifteenth – early sixteenth centuries) which inspired both to pursue the ‘discovery’ of two Indies – a source of spices equivalent to gold in their era, and the gold fields of America. This, in turn, shifted trade in Southern Europe mainly to the trading cities of Lisbon, and Seville. Similarly, trade centres also shifted in the Low Countries. Flanders (following Baldwin III’s death, coupled with its involvement in the French War), turned the trading cities that had initially supported free markets without taxes and customs into the opposite and unproductive. This sparked revolts such as those in Ghent in 1301 and others in Bruges until 1488 – prompting the first migration of merchants and artisans to Brabant who unfortunately adopted the same policies. It led economic warriors back to Antwerp around the fifteenth century, which was unfortunately again destroyed by the anti-Protestant politics of Spain, the siege of the city by its troops, and continued until the 80-year war with the Dutch (1568-1648) which was won by the latter. This victory provided a clear momentum for merchants and artisans to migrate to the Netherlands, with Amsterdam becoming the key trading city – and the early Dutch state emerging as a trading power in Europe.

This was not an entirely new development: since the fifteenth century, the Netherlands had built the backbone of its trade on herring, thanks to the invention of a fish preservation technique called ‘gibbing’ by Willem Beukelszoon from Zeeland in 1386 (However, some historians argue that this is a myth, as the practice of gibbing actually originated in Scandinavia and was later introduced to the Low Countries).[6] As the Dutch population grew due to inward migration, the herring industry reached the peak of its glory in the seventeenth century. The profits from this industry soared to tens of millions of livres, with about 70% of the revenue contributing to the state. These funds were then used by the Netherlands to import raw materials, which were processed by artisans, laying the foundation for the country’s manufacturing industry. This included textiles in Leiden and Haarlem, shipbuilding in Zaandam, ceramics and porcelain in Delft, cheese in Hoorn, and herring in Enkhuizen. The main trading centres were Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Additionally, the wealth of the Dutch in the seventeenth century was also driven by the success of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) in the East Indies, which Huet explored in the following chapters.

Replica ship of the Amsterdam Location: Het Scheepvaartmuseum, Amsterdam. Credits: Eddo Hartmann, © Het Scheepvaartmuseum.

Chapters 4-12 and Sections 1-2 alternately highlight Dutch trade relations with various European countries, detailing the commodities they exported and imported, as well as the strategies employed by the Netherlands in responding to trade policies from other nations that were unfavourable to them. The Netherlands established trade connections with Russia/Moscow and Sweden, both rich in metals for arms production; Norway, known for its timber used in shipbuilding; Denmark, Poland, and Germany, which provided wheat and a variety of natural products such as wool for the textile industry; Italy and France, both renowned for their silk production, with France also famous for its wine; Portugal and Spain, rich in precious metals from their American colonies; England, also known for its wool; and Ireland, whose commodities were in the form of livestock product (each country indeed contributed more than one export commodity, this review highlights the most significant ones). The Dutch, in turn, exported spices acquired from the East Indies and re-exported commodities obtained from other countries — those that met domestic needs — at higher prices for profit. This system not only worked in Europe but was also applied in Asia.

However, this does not mean that Dutch trade in Europe was without obstacles. During the reign of Philip II (1527–98), Spain activated high taxes on the Dutch in its territories – which in turn encouraged the Dutch to resurrect their own trading city (Amsterdam) as well as make voyages to find sources of spices. This then sparked many rebellions (the forerunner of the 80-year war) and when Antwerp fell to the Spanish in 1585, the Dutch responded by blocking access to the Scheldt River – a blockade that lasted 250 years and was only fully lifted in 1863. This action prevented Antwerp from developing further as a trading hub and led to Amsterdam taking its place.[7] In 1651, the British issued the so-called ‘Navigation Act’ which some historians interpret as an attempt by the British to move the European trading entrepôt from Amsterdam to London. According to this law, Dutch ships entering Britain and the Channel were not allowed to transport vital commodities such as spices, sugar, and goods that the Netherlands imported from other European countries – only goods that were truly Dutch were allowed to enter. The application of the act triggered the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652–54).[8] In 1667, under Colbert’s mercantilism, France did the same by imposing high tariffs and import bans on Dutch goods. This, combined with Louis XIV’s invasion, culminated in the Franco-Dutch War of 1672–78.[9] In 1683, Denmark also issued special aggressive tariffs aimed at the Netherlands which then retaliated by stopping imports of goods from Norway (at that time the two countries were part of the combined Kingdom of Denmark and Norway). Realizing that this was detrimental to them, Denmark revoked the policy in 1688.[10]

Walter M. Gibbs, Spices and How to Know Them (Buffalo, N.Y., 1909), plate facing p. 108. Depiction of Cloves. Public domain, via HathiTrust Digital Library.

Chapters 13–15 and sections 3–5, as well as some specific chapters, discuss Dutch trade in the West Indies and Asia (India, East Indies, Sri Lanka, Tonkin/Vietnam, the Arab Region, Japan, and several other areas). This section opens with a flashback of how Europeans, through Arab, Syrian, and Egyptian intermediaries, had been connected to India since the third century AD, benefiting from Italy’s geographical position closest to the sources of these commodities. It was not until Vasco da Gama’s voyage reached Calcutta in 1498 that the route became direct without intermediaries — paving the way for the Portuguese to build a network of fortifications in India (Goa, Malabar, Coromandel), Sri Lanka, and the East Indies (Malacca and the Maluku Islands (Moluccas)). Nearly a century later, the Dutch followed suit, spurred on by a Spanish trade embargo in 1585. The success of Cornelis de Houtman’s voyage to Banten in 1596 was the beginning that led to the establishment of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) in 1602. Unlike the Portuguese, the success of the VOC rested not only on naval power, but also on a very strong institutional foundation. The state’s official charter gave the VOC extraordinary authority — building fortifications, waging wars, making treaties, and even printing its own currency. A great power led directly by the Governor-General controlled by Heeren XVII (the Council of Seventeen) representing the various provinces of the Netherlands, the VOC became a semi-state entity capable of moving flexibly in the global arena. With this power the VOC not only succeeded in displacing the Portuguese from Ceylon, Malacca, Malabar, Coromandel, to Maluku, but also built a much wider trade network, entering Tonkin (Vietnam), trading in the Arab region, and even penetrating the Japanese isolation policy through a limited post in Deshima. The strategy of divide and conquer — i.e. taking advantage of the internal conflicts of local kingdoms — became the key to their dominance, as seen in the Makassar War (1666–69), their efforts to weaken Mataram from the mid-1640s, and the internal conflict in the Sultanate of Banten (1651–82). Moreover, in order to keep the price of spices stable in Europe and the world, the Netherlands limited its quantity by carrying out an extirpation policy – cutting down clove trees around the Maluku Islands, except in two special production sites, namely Ambon and Lease.[11]

Walter M. Gibbs, Spices and How to Know Them (Buffalo, N.Y., 1909), plate facing p. 35. Black Pepper. Public domain, via HathiTrust Digital Library.

Spices were not the only focus of the VOC’s trade in India, Ceylon, and the East Indies. There were at least four groups of commodities spread across several Asian regions that were the object of VOC exports, including: spices (pepper, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon) from the East Indies, India, Ceylon; cotton textiles from India, China, Persia, Turkey; metals and ceramics from Japan, China, the East Indies, Siam; as well as silk from China, India, and Persia. Furthermore, in the West Indies where in 1621 the Dutch established the so-called West-Indische Compagnie (WIC), the main commodities traded were gold, ivory, slaves, leather, and rubber. By adapting the same model/system as the VOC, the WIC trading arena was spread across the coasts of Africa and the Americas. As with the struggle for control of resources and trade routes in India and the East Indies, the Dutch again had to contend with the same main enemies, the Portuguese and Spain.

Huet’s Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois reflects the trajectory of his career. In his introduction Huet combines Catholic idealism with rational thinking about economics. He criticized the socio-economic situation at that time while reminding his readers that the greatness of the nation did not only come from materiality, but also from morality and a higher vision, which could be given by God. As Huet noted, dominance in trade was essential to the early modern state:

‘To these I shall add, that a great State cannot flourish, or indeed be at Peace, if it has not a great Trade; for ‘tis only by means of Trade it can draw to its self riches and Plenty, without which it can undertake nothing advantageous, either to aid and assist its Allies, or extend its Limits’.[12]

Huet looked to a leader who would lead France to economic dominance:

‘Heaven could once have given us, and yet might have given us another Jaques Couer, and then we should have entertained greater Hopes than ever to bring the Trade of France to its highest Pitch, and make our Nation the most flourishing in the World. The Merchants of France, to accomplish this, want only an experienced Leader; a Person of much Knowledge, one that has a great Foresight, an enterprizing Genius, and continual Application and Perseverance; a Person of great Credit and Power, that he may protect those who traffick under him, and are his Commissioners, in whatever Place of the World’.[13]

Map of the East Indies published by Nicolaas Visscher II (1649–1702) taken from v.4 of the Atlas of Dirk van der Hagen that is held in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague. The map shows the entire trading region of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The nationalism apparent in such statements is hardly surprising, but interestingly, Huet describes conflict between the VOC and kingdoms in the East Indies from a Dutch perspective. An example of this pro-European bias may be seen in his account of the following incident:

‘The reasons that led the Company to make war against the Macassarians were the greatness of the kings of that country, their power which increased daily, and their underhanded workings against the Company’s interests, to the point that the Company was in perpetual anxiety about how to preserve their possessions in those kingdoms. Additionally, the frequent murders and robberies committed by that nation, both against the officers and servants of the Company as well as their friends and allies, gave them more than sufficient provocation to take up arms against those people. Therefore, the Company was not hesitant to send a strong force against them’.[14]

This interpretation clearly differs from the Indonesian historical narrative which tells a different story of how the VOC tried to expel other foreign traders who had previously co-operated with Makassar. The VOC even made two attacks first on the Kingdom of Gowa with the help of the Kingdom of Bone, whose leader sought revenge after being conquered by the first kingdom. This, in turn, meant that the killing of anyone who supported the VOC could be labelled as self-defence by the Makassar side – before they were finally defeated and had to surrender with the Treaty of Bongaya (1667).[15]

It is understandable that the core focus of this book is on Dutch trade, but since it also compares the Dutch with other European countries, the discussion becomes broader and more complex. One intriguing aspect of the book is Huet’s tendency to refer to the Dutch East India Company as East India Company without specifying ‘Dutch’. Here are the examples:

‘Some small time after their East-India Company was settled, having a great deal of Money and Seamen unemployed, they began to talk of trading to the West-Indies…: But those who wished for Peace, believing that an Establishment of the Dutch in America would raise invincible Obstacles, hinder’d the Execution of that Project. The Truce of twelve Years, which they made with Spain in the Year 1609, expiring in the Year 1621, they began to revive that Project; and the States-General having approv’d it, they regulated every thing that might any wise have relation to the Establishment of the New West-India Company, in hopes that their Republic might reap no less Benefit and Advantage by this, than they had by the East-India Company; and all these Regulations were made and resolved upon the 20th Day of June, in the same Year 1621.This New General Company, which was set up upon their Plan of that of the East-Indies, was composed of several particular Companies, that traded on the Coasts of Africa and America’.[16]

Given how strongly the term ‘East India Company’ is associated with the English company, omitting ‘Dutch’ can easily lead to confusion. It feels like an important historical identity is being glossed over, especially considering how crucial national distinctions were in colonial trade dynamics.

Overall, this book offers a complex discussion on the rise and expansion of Dutch trade from its early beginnings up to the seventeenth century. Presented in a chronological manner, it takes readers through the rise of Dutch economic dominance, the evolving strategies they employed to expand that monopolistic dominance, and the range of commodities they exported and imported across four continents — Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. As readers, we are led to affirm Huet’s claim that the Dutch were the most skilled trading nation of their time, considering how — epically — they managed to create full-spectrum dominance over the spice trade by locking production, distribution, and pricing into their own hands. In the hands of the Dutch, spices were not merely commodities, but tools of global control.

* All translations are from the 1718 English translation of Huet’s Memoirs sur le Commerce des Hollandois. The English translation was not collected by Worth.[17]

Text: Ms Apriliya Rida Nabila (MA in Public History, UCD).

Sources:

Arief, Ruslan, et al., ‘Makassar War in the Perspective of the Indonesian Total War’, Journal of Social and Political Sciences, 4, no. 2 (2021), 230–8.

Bes, Lennart, Edda Frankot, and Hanno Brand (eds) Baltic Connections: Archival Guide to the Maritime Relations of the Countries around the Baltic Sea (including the Netherlands) 1450-1800, 3v. (Leiden and Boston, 2007).

Di Paola, Maria Teresa, ‘François Changuion, ‘à la tête de Juvenal’ in the Strand’, The Huguenot Society Journal, 31 (2018), 34–48.

Farnell, J. E., ‘The Navigation Act of 1651, the First Dutch War, and the London Merchant Community’, The Economic History Review, 16, no. 3 (1964), 439–54.

Gibbs, Walter M., Spices and How to Know Them (Buffalo, N.Y., 1909).

Huet, Pierre-Daniel, Memoires sur le Commerce des Hollandois, dans tous les Etats et Empires du Monde … (Amsterdam, 1717).

Huet, Pierre-Daniel, and Robert Samber (tr.), Memoirs of the Dutch Trade in All the States, Kingdoms, and Empires in the World … (London, 1718).

Kurtzleben, Jeri, ‘The Economic Policies of Jean-Baptiste Colbert’, Draftings In, 9, no. 3 (1997), 20–7.

Mansyur, Syahruddin, ‘Perdagangan Cengkih Masa Kolonial dan Jejak Pengaruhnya di Kepulauan Lease = Clove Trade during Dutch Colonization and its Influence in Lease Islands’, Kalpataru: Majalah Arkeologi, 22, no. 1 (2013), 43–60.

Rijks, Marlise, ‘A Taste for Fish: Paintings of Aquatic Animals in the Low Countries (1560–1729)’, in Smith, Paul J., and Florike Egmond (eds), Ichthyology in Context (1500–1880) (Leiden and Boston, 2023), pp 259–97.

Saddington, Justin, ‘The Journal of Major General Robert Stearne of the Royal Regiment of Ireland’, British Journal for Military History, 9, no. 2 (July 2023), 13–30.

Shelford, April G., Transforming the Republic of Letters: Pierre-Daniel Huet and European Intellectual Life, 1650–1720 (Rochester, N.Y. and Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2007).

Unger, Richard W., ‘Dutch Herring, Technology, and International Trade in the Seventeenth Century’, The Journal of Economic History, 40, no. 2 (1980), 253–79.

Wintle, Michael, An Economic and Social History of the Netherlands, 1800–1920: Demographic, Economic and Social Transition (Cambridge, 2000).

[1] Di Paola, Maria Teresa, ‘François Changuion, ‘à la tête de Juvenal’ in the Strand’, The Huguenot Society Journal, 31 (2018), 37–40.

[2] Saddington, Justin, ‘The Journal of Major General Robert Stearne of the Royal Regiment of Ireland’, British Journal for Military History, 9, no. 2 (July 2023), 13–30.

[3] Shelford, April G., Transforming the Republic of Letters: Pierre-Daniel Huet and European Intellectual Life, 1650–1720 (Rochester, N.Y. and Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2007), pp 1–11.

[4] Huet, Pierre-Daniel, and Robert Samber (tr.), Memoirs of the Dutch Trade in All the States, Kingdoms, and Empires in the World … (London, 1718), p. i. All quotations are from this English translation.

[5] Ibid., p. xii.

[6] Unger, Richard W., ‘Dutch Herring, Technology, and International Trade in the Seventeenth Century’, The Journal of Economic History, 40, no. 2 (1980), 255–6; Rijks, Marlise, ‘A Taste for Fish: Paintings of Aquatic Animals in the Low Countries (1560–1729)’, in Smyth, Paul J., and Florike Egmond (eds), Ichthyology in Context (1500–1880) (Leiden and Boston, 2023), p. 264.

[7] Wintle, Michael, An Economic and Social History of the Netherlands, 1800–1920: Demographic, Economic and Social Transition (Cambridge, 2000), p. 149.

[8] Farnell, J. E., ‘The Navigation Act of 1651, the First Dutch War, and the London Merchant Community’, The Economic History Review, 16, no. 3 (1964), 443–4.

[9] Kurtzleben, Jeri, ‘The Economic Policies of Jean-Baptiste Colbert’, Draftings In, 9, no. 3 (1997), 25.

[10] Bes, Lennart, Edda Frankot, and Hanno Brand (eds), Baltic Connections: Archival Guide to the Maritime Relations of the Countries around the Baltic Sea (including the Netherlands) 1450–1800, 3v. (Leiden and Boston, 2007), i, pp 14–5.

[11] Mansyur, Syahruddin, ‘Perdagangan Cengkih Masa Kolonial dan Jejak Pengaruhnya di Kepulauan Lease = Clove Trade during Dutch Colonization and its Influence in Lease Islands’, Kalpataru: Majalah Arkeologi, 22, no. 1 (2013), 47; Gibbs, Walter M., Spices and How to Know Them (Buffalo, N.Y., 1909), pp 108–10.

[12] Huet and Samber, Memoirs of the Dutch Trade (London, 1718), pp ii–iii.

[13] Ibid., p. x.

[14] Ibid., p. 203.

[15] Arief, Ruslan, et al., ‘Makassar War in the Perspective of the Indonesian Total War’, Journal of Social and Political Sciences, 4, no. 2 (2021), 230–8.

[16] Huet and Samber, Memoirs of the Dutch Trade (London, 1718), p. 186.

[17] Huet, Pierre-Daniel, and Robert Samber (tr.), Memoirs of the Dutch Trade in All the States, Kingdoms, and Empires in the World … (London, 1718).